Researching Gestalt Therapy for Anxiety in Practice-Based Settings

A Single-Case Experimental Design1

Pablo Herrera, Illia Mstibovskyi, Jan Roubal & Philip Brownell

Psychotherapie-Wissenschaft 9 (2) 53b–68b 2019

www.psychotherapie-wissenschaft.info

https://doi.org/10.30820/1664-9583-2019-2-53b

Abstract: Despite the proven efficacy of CBT treatments for anxiety disorders, between 33 % and 50 % of patients do not respond or drop out of these treatments. Gestalt therapy has claimed to be an effective alternative, but there is little empirical evidence on its efficacy with anxiety. The Single-Case Experimental Design with Time Series Analysis was used as a practice-oriented study of efficacy. Evidence on ten clients diagnosed with anxiety disorders is presented, supporting the claim that Gestalt therapy can be a useful treatment for this. Detailed analysis of one case illustrates the changes in symptom and well-being scores, indicating turning points during the therapy. The paper discusses the use of this methodology for creating a practice-oriented research network.

Key words: Anxiety, Gestalt therapy, single-case, time series experimental design, practice-oriented research

Decades of systematic research has proven the efficacy of psychotherapeutic treatments, including the treatment of patients suffering from different forms of anxiety disorders (Roth & Fonagy, 2013). There is a vast body of evidence about the efficacy of behavioral and CBT interventions, which are considered the treatment of choice for most of the anxiety disorders (Hollon & Beck, 2013). However, these approaches do not seem to be sufficiently helpful to a substantial group of patients. Only 50 % of CBT patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder achieve high end-state functioning, about 30 % of PTSD patients drop out of CBT interventions, and at least one third of patients suffering from social anxiety do not respond to CBT interventions (Lambert, 2013). Looking for alternative evidence-based approaches that could complement the prevalent CBT treatment is a way of widening the possibilities of psychological help for patients with anxiety.1

Despite having a long history of working with anxiety, humanistic-experiential treatments have not shown robust evidence of their efficacy for anxiety disorders (Angus et al., 2015; Elliot et al., 2013). For example, a recent review of empirical evidence on humanistic therapies concluded that they appear to be less effective than CBT for anxiety difficulties and that they should only be considered for clients who have already tried or refused CBT (Angus et al., 2015). Although current results suffer from negative research allegiance and sometimes a misrepresentation of humanistic therapies (Elliot et al., 2013), it seems that clients with anxiety disorders may respond better to more structured treatments and that perhaps «process experiential therapies have not been implemented in an effective manner with this client population» (ibid., p. 8). This requires further study on this particular population.

Current research on the effectiveness of humanistic-experiential therapies with anxiety disorders is very limited. Most existing studies address person-centered therapy, with none on focusing-oriented therapy, a few very recent open trials on Emotion Focused Therapy (Shahar et al., 2017; Timulak et al., 2017; Watson & Greenberg, 2017), and only one study on Gestalt therapy (Elliot et al., 2013). Further research on this topic could help establish the efficacy of more structured humanistic-experiential modalities (e.g. Gestalt therapy, EFT), and also serve to better understand anxiety difficulties from a humanistic-experiential point of view. As Elliot (2013, p. 12) concluded:

«I have no doubt that PCE [Person Centered & Experiential] therapies have a great deal to contribute to helping clients with anxiety difficulties, particularly if we invest the time and energy needed to carry out research that truly represents what we do and if we collaborate with our clients to enhance the appropriateness and effectiveness of what we have to offer.»

Anxiety from the Gestalt therapy perspective

Gestalt therapy is a phenomenological, existential and relational approach with the holistic and dynamic organism-environment field as its basic anthropology. The theory and practice of Gestalt therapy provide differentiated approaches in diverse clinical settings with various clinical populations (Francesetti et al., 2013), including the treatment of anxiety (Robine, 2013).

Anxiety seen from the Gestalt therapy perspective is a holistically experienced state of organism arousal, which lacks support for an action directed towards an expression of a need. Anxiety is not seen as a pathology to be simply eliminated, but rather as a sign that the organism’s vital arousal has been interrupted and with appropriate therapeutic support can be redirected towards growth (Ceballos, 2014). Neurotic anxiety is produced when certain organismic needs are considered unacceptable, so their expression and associated arousal is systematically interrupted by fixed relational patterns, which restrict the flexibility and creativity of the individual’s potential for reacting to different situations in a way that would meet her/his needs here and now (ibid.; Herrera, 2016). Neurotic anxiety can also be resolved when the person is able to be in the here and now, instead of fantasizing and catastrophizing about the future (Perls, 1969).

The Gestalt perspective is inherently relational. Anxiety symptoms experienced in the body are understood as individual expressions of relational suffering (Roubal et al., 2013), when the individual’s process of contacting with other people lacks spontaneity and fluidity. In such cases, the style of interpersonal contact is rigidly distorted by fixed relational patterns, and needs are not being met within relationships. Relating to others and oneself according to a need to «do the right thing» could be one example of such distortions, narrowing the possibilities of experience and of creative adjustment (Robine, 2013). The flow of figure/ground formation becomes disrupted, because the person fears taking risks to find creative ways toward mutually satisfactory contact. While the arousal is present, the organism is inhibited or even paralyzed.

In therapy, support is needed to transform anxiety into fluid and creative excitement. The support comes from the therapeutic relationship, in which the needs of the client are recognized and validated. In the safe therapeutic situation, the client’s inhibition is reduced and the arousal of her/his organism can be directed towards an expression of relationally felt needs. A client’s experience could then be: «With the therapist I can risk being my way without judging it as right or wrong». The paralyzing anxiety is transformed into an excitement of discovering new creative ways of contact. The client experiments with them first in the safe psychotherapeutic relationship and later also with other people.

The need for alternative methodologies to do efficacy research in Gestalt therapy

One of the main challenges to empirically support a treatment model resides in the methodology used for research (Borckardt et al., 2008). The Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) design, used for efficacy studies is considered the «gold standard» to establish causality between type of treatment and patient results. However, it presents several difficulties, mainly: (1) it is too expensive and difficult to implement, being a group methodology out of reach for most practitioners and researchers; (2) it generates «laboratory» conditions that differ greatly from the usual context in which psychotherapy is delivered; (3) it reduces patients’ complex realities and problems to a diagnostic label; (4) it only depicts results, not allowing the researcher to understand the change process or change mechanisms involved with the process; and (5) the condition of homogeneity it imposes and assumes about clients, therapists and treatments have led to statistical and conceptual problems, and have been recognized as the main obstacle to the development of research in psychotherapy (Carey & Stiles, 2015; Silberschatz, 2017; Tschuschke et al., 2010).

These are important limitations for conducting efficacy research on Gestalt therapy and other humanistic approaches, because Gestalt researchers are not usually in academic positions that would allow them to conduct group studies with student populations or to get funding, and because the humanistic tradition has epistemological discrepancies with the laboratory’s reductionist ways of doing research (Angus et al., 2015). Facing this reality, Gestalt therapy teaching and practice mainly continues to be based on clinical intuitions and anecdotal testimony not backed up by empirical research. As a result, health care policies that require empirical validation do not include Gestalt therapy among the treatment alternatives for patients, leaving them without this potentially beneficial treatment option.

The Single-Case Time Series Design

In this context of practical and epistemological limitations, the American Psychological Association (APA) has agreed that RCTs should not be the only option for studying efficacy and empirically supporting a treatment method (APA, 2006). It proposes the Single-Case time series design (SCTS) as a valid alternative (ibid.; Chambless et al., 1998; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001) and states that a large series (>9) of single-case experimental studies would be just as acceptable as two between-group experiments for indicating that a therapy is well-established in nature (Chambless et al., 1998). In the same vein, Borckhardt et al. (2008, p. 77) pointed out that the

«practitioner-generated case-based time-series design with baseline measurement fully qualifies as a true experiment and that it ought to stand alongside the more common group designs (e.g., the randomized controlled trial, or RCT) as a viable approach to expanding our knowledge about whether, how, and for whom psychotherapy works.»

In the SCTS design, a single case is studied longitudinally, along different phases before, during and after the psychotherapeutic intervention. It is an experiment because the patient is being compared to him or herself with and without intervention, collecting baseline data to assess the patient’s problems (dependent variable) without intervention (control condition), and later collecting data during and after the intervention for comparison (intervention condition). Thus, the patient functions as his or her own control. The method qualifies as time series analysis because data is collected continuously with regular daily measurements and is then analyzed considering auto-correlation and possible confounding effects on effectiveness such as natural remission due to the passage of time.

The SCTS is advantageous for studying the efficacy of psychotherapy models which cannot, or prefer not, to use the RCT methodology. Its utility has been proven in various research projects from behavioral activation during inpatient psychiatry (Folke et al., 2015; Silberschatz, 2017), to tracking school-based communication in autism spectrum children (Whalon et al., 2015), to CBT for comorbid anxiety and depression (Hague et al., 2015). The design of this present study also corresponds to the series of N-of-1 trials followed by meta-analyses, which is now becoming popular in healthcare instead of RCT (Mengersen et al., 2015; Punja et al., 2016).

For process-outcome studies the SCTS can be combined with qualitative research methods, enabling detailed and continuous information about the client’s change process before, during and after psychotherapy. This can indicate which therapy sessions had a positive, neutral or negative impact on the client’s presenting problems. It can illustrate how the change process unfolds over time, and pinpoint the phases or critical turning points in the process of change.

In sum, single-case experimental design with time series analysis provides an acceptable alternative to random controlled treatments using groups (Smith, 2012; Kratochwill & Levin, 2010), and provides valuable additional benefits. SCTS are more manageable and less expensive than group designs (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). They are less intrusive, allowing practitioner-researchers to study the way they normally work in their daily practice. They allow inferences of causation in the psychotherapy change process.

The aim of this study is to provide evidence of the efficacy of Gestalt therapy with clients diagnosed with anxiety. The study also demonstrates an application of SCTS in a practice based research network.

Methodological Framework

Single-Case Experimental Design

In this A-B-A Single-Case Experimental Design with Time Series Analysis, there were three phases: (1) an initial baseline phase without therapy (two weeks, starting at the assessment session «0» and ending before the first therapy session), (2) a therapy phase (a minimum of eight Gestalt therapy sessions, with the maximum length depending on each specific case), and (3) a follow up phase (two weeks, starting at the final therapy session).

Measures

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI 6.0; Sheehan et al., 1998) is a short structured interview used to assess seventeen common Axis I disorders using DSM-IV criteria. It was administered by a psychotherapist or psychiatrist with DSM-IV training to ascertain the client’s diagnosis.

The Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Hamilton, 1959) is a structured interview used to assess the client’s current somatic and psychic anxiety. It uses the following cutoff scores: (1) 0–5 no anxiety, (2) 6–14 low anxiety, (3) 15–30 moderate anxiety and (4) ≥ 31 severe anxiety. It presents good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.79–0.86) and inter-rater agreement (r=0.74–0.96).

The Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2; Lambert et al., 1996) is a short self-report questionnaire used to assess the client’s general wellbeing. It has three scales: symptomatic distress, interpersonal functioning, and social role performance. The cutoff score is 73, and the reliable change index (RCI) is ≥17, based on the Chilean adaptation by von Bergen & de la Parra (2002).

The Beck Depression Instrument (BDI-1; Beck, 1978) is a short self-report questionnaire used to measure the intensity, severity, and depth of depression. Cutoff scores are (1) 0–9 minimal depression, (2) 10–18 mild depression, (3) 19–29 moderate depression, (4) 30–63 severe depression.

The Target Complaints (Battle et al., 1966) is an individualized self-report measure of 3–4 main, specific, idiosyncratic problems, which are identified and co-constructed between client and therapist during session «0». The score range is 1–10 and each complaint is analyzed individually. They should be concrete, quantifiable, frequent, stable without treatment, and relatively independent of each other. These complaints are used for the time series analysis. The reliability of this measure has been considered reasonably high, but it lacks more validity data (Deane et al., 1997).

The Therapist Experience Journal is a record of the therapist’s experiences and notes of the therapy and research process based on the CSEP-II Experiential Therapy Session Form (Elliot, 2003), the results of which are not used in this particular paper.

Participants

Clients. The psychotherapy was conducted in an individual setting, in both private practice and public health contexts. The clients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) Presence of an anxiety disorder according to the MINI, or a ≥15 score in the Hamilton Anxiety Scale; (2) No paranoid or psychotic symptoms; (3) No problem that required urgent psychotherapeutic intervention; (4) No other parallel therapy for the same target complaints between three weeks earlier and three weeks after the first therapy session. For ethical reasons, the participants were allowed to participate in other forms of therapy after this 3 week period; however, no client reported having entered another form of therapy after starting the psychotherapy sessions. Table 1 shows a more detailed description.

|

Patient Nº |

Age & gender |

Diagnosis |

Hamilton score |

Nº of sessions |

|

1 |

39 |

anxiety disorder |

13 (mild) |

14 |

|

2 |

30 |

generalized anxiety |

21 (mod.) |

15 |

|

3 |

23 |

anxiety disorder |

17 (mod.) |

12 |

|

4 |

26 |

alcohol abuse, agoraphobia, depression |

19 (mod.) |

18 |

|

5 |

23 |

panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety |

29 (mod.) |

40 |

|

6 |

29 |

mixed anxiety and depression disorder |

17 (mod.) |

19 |

|

7 |

37 |

mixed anxiety and depression disorder |

39 (severe) |

8 |

|

8 |

24 |

anxiety disorder |

25 (mod.) |

11 |

|

9 |

24 |

adaptation disorder with anxiety symptoms |

23 (mod.) |

16 |

|

10 |

26 |

panic disorder without agoraphobia |

24 (mod.) |

20 |

Tab. 1: Description of the Sample

Therapists. Every client was treated by a different therapist (8 female, 2 male). All therapists were master’s degree students (Gestalt therapy master’s degree training program, Center of Gestalt Psychotherapy of Santiago) in their third year of training, and participation in the study was one of the alternatives for their final thesis (the other was doing a theoretical paper). Each therapist had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) five or more years of psychology, social work or psychiatry undergraduate training, (2) two or more years (at least 360 hours) of Gestalt therapy graduate training, (3) access to supervision with a Gestalt-trained supervisor for the duration of the treatment.

Treatment Fidelity. Treatment fidelity was based on psychotherapy training and supervision of the therapists, which was conducted in the Gestalt therapy modality.

The selection procedure. Clients that met the inclusion criteria were contacted by the therapists via telephone or email and invited to participate in the study. The first ten cases that completed a minimum of eight therapy sessions were chosen for this study. After collecting the data for these ten cases, another therapist reported a dropout case that attended fewer than eight sessions, which was not included in this study.

Ethics. Before the initial assessment session (session 0), clients were informed about the general design and its implications and in session «0» they signed an informed consent. All data were stored anonymously, in accordance with the Universidad de Chile regulations.

Data collection procedure

Baseline Phase (A). At the Session 0, the therapist applied the first set of data collection instruments (MINI 6.0., OQ-45 and Hamilton Anxiety Scale), and the target complaints (TC) were identified collaboratively with the client. After the Session 0, the patient started recording the daily target complaints. After two weeks (14 daily measurements), the therapy phase started with the first psychotherapeutic session.

Therapy Phase (B). The recording of the daily target complaints continued. After every session therapists completed the therapist experience journal and patients completed the OQ-45. All sessions were video/audio recorded.

Follow up Phase (A). The follow up phase started with the final therapy session, in which the OQ-45 and Hamilton anxiety scales were applied. The recording of the daily target complaints continued for two weeks after the final session. After six months, an independent interviewer contacted the client and applied the BDI-1, OQ-45 and Hamilton anxiety scale in a follow-up session.

Data Analysis

The Single-Case Experimental Design (Smith, 2012) with time series analysis was used, comparing the Target Complaints (TC) scores in the baseline and follow-up phases. Quality standards for SCTS methodology were followed: (1) Both visual and statistical analysis (and that the statistical instruments account for autocorrelation) were used; (2) Target complaints were complemented with standard outcome or symptom measures; (3) Non-therapy-related trends that could explain the patient’s improvement were controlled; and (4) Effect size data were considered for future aggregation of multiple single-case analysis and meta-analysis (Borckardt et al., 2008; Borckardt & Nash, 2014; Tate et al., 2013; Wendt & Miller, 2012). Data analysis was conducted to provide answers to the following three research questions:

Research question I: Is there pre-post improvement, and if so, how great? Three different indicators were used: (1) visual analysis, comparing the target complaint (TC) scores during the three phases; (2) test for level change comparing baseline and follow up phases, using r coefficient (Pearson’s correlation of TC with phase vector, p<0.05) to calculate Effect Size (ES). As suggested by Borckardt et al. (2008), this was calculated using their own Simulation Modeling Analysis (SMA) software, freely available at http://clinicalresearcher.org and specially developed for the small number of observations and consideration of the time series autocorrelation; (3) mean baseline reduction (MBLR, calculated by subtracting the mean follow-up value from the mean baseline value, dividing by the mean baseline value and then multiplying the result by 100), as one of the most frequently reported and meritorious methods for calculating effect sizes for single-case designs (Campbell, 2003; Olive & Smith, 2005).

Research question II: Is the change clinically meaningful? If there was evidence of pre-post improvement, the analysis focused on how clinically meaningful that change was found to be. Two indicators were used: (1) OQ-45 scores at session 0, final session and follow up session were compared, considering the Chilean reliable change index of ≥17; (2) Hamilton anxiety scale and BDI scale scores at session 0, final and follow up were compared.

Research question III: Can the improvement be attributed to the therapy process? To confirm that the improvement was due to the intervention and not a product of a downward trend in target complaint ratings that began in the baseline phase and just continued in the therapy and follow up phases, the following procedure was used:

1. Examining whether a trend exists, using a standard method of linear regression analysis: R-squared value, p-value of the F-test of the overall regression significance. If there was no trend, then the answer to this research question was «yes». If there was a trend then:

2. Calculating the ES that arises when deleting the influence of the trend, using SMA partial correlation analysis controlling for influence of the observed trend (this procedure measures the same Pearson’s r under the condition that the correlation of the target complaint and the linear trend is removed). If the resulting ES was statistically significant, then the answer to this research question was also «yes». If it was not significant then:

3. Carrying out visual analysis of the entire process, as recommended by Borckardt & Nash (2014). If there were obvious peculiarities of the process that affected the ES and were different from the trend, then the answer was also «yes». If not, the answer to the research question was «no».

Other considerations for the data analysis. For filling in missing data the EM Procedure (Expectation-Maximization Algorithm) was used, a method well-suited to such time-series observations given the fact that power sensitivity falls when autocorrelation is large (Smith et al., 2012). Meta-analysis was an important part of our study because it allows us to: (1) calculate effect sizes (ES) for all treatment complaints (TC) and also to form Glass’ Δ, comparing them with the ES values obtained by the SMA, (2) obtain an aggregated ES values for each of the ten cases; and (3) calculate aggregated ES values for the research as a whole and determine the place of each case in the context of the others (Manolov & Solanas, 2008). For this purpose, we calculated the standardized mean differences for each TC with Glass’ Δ (Glass et al., 1981) as recommended by Beretvas & Chung (2008), using unweighted averages (see Manolov et al., 2014). As is known, unlike the group design, in a SCTS the standardized mean differences do not have benchmarks and their values are determined by the specificity of each study.

Results

Our results provided evidence of the efficacy of Gestalt therapy in this study. A meta-analysis of all researched cases and an example of the more detailed results in one selected case are also presented to supplement answers to the three research questions. Table 2 provides detailed mean and SD scores for all TC.

|

Nr. |

TC (nº and text) |

Baseline |

Therapy |

Follow up |

||||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|||

|

1 |

N=13 |

N=155 |

N=14 |

|||||

|

1 Don’t know how to show my true feelings |

5,1 |

0,3 |

4,3 |

1,7 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

2 When in a couple I’m rigid, it’s difficult to get involved emotionally |

4,4 |

1,0 |

4,6 |

1,9 |

1,2 |

0,4 |

||

|

3 Distant relationship with parents |

4 |

1,1 |

2,7 |

1,3 |

1,1 |

0,4 |

||

|

4 Can’t handle well my anger |

4,5 |

1,1 |

1,6 |

1,0 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

2 |

N=17 |

N=149 |

N=12 |

|||||

|

1 Fear of Success |

3,3 |

1,0 |

2,7 |

1,0 |

2,2 |

0,4 |

||

|

2 Anxiety |

3,7 |

0,8 |

2,9 |

1,1 |

2,3 |

0,6 |

||

|

3 Bad relationship with mother |

2,1 |

0,9 |

1,4 |

0,6 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

3 |

N=16 |

N=120 |

N=11 |

|||||

|

1 I feel sad about not contacting others |

3,9 |

0,9 |

2,7 |

1,2 |

1,6 |

0,9 |

||

|

2 I feel guilty if I do not meet my own demands |

5,1 |

0,8 |

3,5 |

1,5 |

2,1 |

0,8 |

||

|

3 I avoid the expression of anger |

3 |

1,3 |

2,2 |

1,1 |

1,5 |

0,8 |

||

|

4 |

N=13 |

N=148 |

N=14 |

|||||

|

1 I’m not sufficient to my family |

4,5 |

1,0 |

2,5 |

1,3 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

2 I’m desperate when idle |

4,8 |

1,5 |

2,4 |

1,4 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

3 I feel frequently anguished |

3,8 |

1,1 |

2,2 |

1,5 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

5 |

N=17 |

N=238 |

N=26 |

|||||

|

1 I cannot establish limits with my ex |

5,9 |

1,3 |

3,9 |

2,0 |

1,6 |

1,2 |

||

|

2 I cannot relate in a friendly way with others, |

4,8 |

1,9 |

2,5 |

1,9 |

1,2 |

0,6 |

||

|

3 Anxiety: I cannot accept things that happen, |

5,9 |

1,6 |

3,7 |

2,1 |

1,6 |

1,3 |

||

|

6 |

N=20 |

N=195 |

N=11 |

|||||

|

1 Difficulty enjoying things |

4,2 |

0,8 |

1,8 |

0,8 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

2 Not being able to control myself with shopping and food |

7 |

0,0 |

5,5 |

0,6 |

5 |

0,0 |

||

|

3 Not accepting my body |

4,8 |

0,7 |

3,4 |

0,9 |

2 |

0,0 |

||

|

7 |

N=14 |

N=72 |

N=14 |

|||||

|

1 I do not feel safe as a mother |

4,5 |

1,4 |

3,3 |

1,9 |

1,5 |

0,5 |

||

|

2 I cannot tolerate the abuse in my workplace |

3,9 |

1,7 |

4,4 |

1,4 |

5,1 |

1,6 |

||

|

3 I can hardly face life with my family divided |

4 |

1,5 |

3,4 |

1,4 |

1,1 |

0,3 |

||

|

8 |

N=17 |

N=93 |

N=68 |

|||||

|

1 Fear of failing to meet other’s expectations |

7,2 |

1,0 |

5 |

2,3 |

2,5 |

1,5 |

||

|

2 Afraid to make a mistake |

6,5 |

1,2 |

3,7 |

1,9 |

2 |

1,7 |

||

|

3 Rejection of herself |

6,1 |

1,8 |

5 |

1,8 |

2,7 |

1,7 |

||

|

9 |

N=14 |

N=187 |

N=15 |

|||||

|

1 I feel insecure in front of people |

6,9 |

1,0 |

3,7 |

1,6 |

1,5 |

0,6 |

||

|

2 I have fear of being poorly valued by people |

7,1 |

1,1 |

3,5 |

1,6 |

1,6 |

0,7 |

||

|

3 I have trouble being sexually uninhibited or free |

8,2 |

1,1 |

4,2 |

2,1 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

10 |

N=14 |

N=169 |

N=14 |

|||||

|

1 I don’t know which way to go, I constantly question what I’m doing |

5,7 |

2,0 |

4,2 |

1,9 |

1,9 |

0,5 |

||

|

2 I have no feelings, things don’t affect me like they used to |

7,5 |

1,3 |

2,1 |

1,3 |

1 |

0,0 |

||

|

3 When things don’t work out for me, |

8,6 |

1,0 |

5 |

2,7 |

1,1 |

0,5 |

||

Tab. 2: Description of Target Complaints for all cases

Research question I: Is there pre-post improvement, and if so, how large?

As shown in Table 3, in almost every patient all the target complaints showed therapeutic change between the baseline and follow up phases. The only exception was target complaint No. 2 (TC2) of patient 7: «I cannot tolerate the abuse in my workplace». This specific TC showed a small worsening (r=+0.353, p=0.4546), starting at 3.9 (baseline mean) and finishing at 5.1 (follow up mean). We can interpret this as a problem in the definition of t his Target Complaint.

All three indicators confirmed the presence of change in the remaining 30 target complaints. MBLR scores ranged between 28 % and 88 %; Pearson’s correlation of TC with phase vector showed values between -0.585 and -0.996 (TC2 of Patient 6 has a -1.00 r value but is a special case with complete lack of variation in both phases); and visual analysis showed various degrees of improvement, both gradual (e.g. Patient 4, TC2) and sudden (e.g. Patient 1, TC1). All raw data (including TC scores and graphics for every TC) are openly available,2 as in this paper we will present only a few examples of the TC graphics.

Of the 30 TC which showed therapeutic change, in 21 TC this change was large (MBLR >65 %; r<-0.749; p<0.05; plus notable change in the visual analysis). In 6 TC the change was of medium size (MBLR >51 %; r<-0.611; p<0.05; plus significant change in the visual analysis). In the remaining 3 TC the change was considered small (MBLR >28 %; r<-0.585; p<0.05; plus noticeable change in the visual analysis).

|

Is there pre-post change, and if YES, how large? |

Is that change attributable to the therapy? |

|||||||

|

Patient nº |

TC nº |

r und p in SMA |

MBLR (%) |

Visual analysis |

Yes/No? Size |

Overall Trend (R2)* |

xy/z and p in SMA |

Yes/No? |

|

1 |

1 |

-0.996 0.0001 |

80 |

Big improvement in last weeks of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

No |

YES |

|

|

2 |

-0.914 0.0002 |

72 |

Big improvement in last weeks of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

No |

YES |

||

|

3 |

-0.882 0.0001 |

71 |

Stable improvement during therapy phase |

YES, LARGE |

0.536 |

-0.733 0.0206 |

YES |

|

|

4 |

-0.920 0.0012 |

78 |

Quick improvement during baseline up to the first part of therapy phase |

YES, LARGE |

0.617 |

-0.673 0.163 |

DEBATABLE |

|

|

2 |

1 |

-0.585 0.0216 |

34 |

Slow improvement during therapy |

YES, SMALL |

No |

YES |

|

|

2 |

-0.697 0.0036 |

39 |

Slow improvement during therapy |

YES, SMALL |

No |

YES |

||

|

3 |

-0.624 0.0244 |

52 |

Small improvement during baseline and start of therapy |

YES, MEDIUM |

No |

YES |

||

|

3 |

1 |

-0.765 0.0022 |

55 |

Gradual improvement during therapy |

YES, MEDIUM |

0.454 |

-0.67 0.0148 |

YES |

|

2 |

-0.862 0.002 |

51 |

Gradual improvement during therapy |

YES, MEDIUM |

0.563 |

-0.805 0.0076 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.611 0.0148 |

52 |

Gradual improvement during therapy |

YES, MEDIUM |

No |

YES |

||

|

4 |

1 |

-0.939 0.0001 |

78 |

Gradual but not steady improvement during therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.574 |

-0.771 0.0864 |

YES |

|

2 |

-0.892 0.0002 |

79 |

Gradual improvement during therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.653 |

-0.686 0.0438 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.881 0.0012 |

74 |

Gradual and very irregular improvement during first half of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.603 |

-0.572 0.1614 |

DEBATABLE |

|

|

5 |

1 |

-0.871 0.0001 |

73 |

Very irregular improvement |

YES, LARGE |

0.448 |

-0.775 0.0062 |

YES |

|

2 |

-0.820 0.0002 |

76 |

Very irregular improvement |

YES, LARGE |

0.375 |

-0.722 0.0084 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.839 0.001 |

73 |

Very irregular improvement |

YES, LARGE |

0.394 |

-0.749 0.0052 |

YES |

|

|

6 |

1 |

-0.931 0.0002 |

76 |

Gradual improvement |

YES, LARGE |

0.726 |

-0.836 0.0152 |

YES |

|

2 |

-1.000 0.0001 |

28 |

Small gradual improvement |

YES, SMALL |

0.784 |

-1 0.0001 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.926 0.0001 |

58 |

Gradual but irregular improvement |

YES, |

0.537 |

-0.844 0.004 |

YES |

|

|

7 |

1 |

-0.828 0.0086 |

67 |

Steep improvement in first half of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

No |

YES |

|

|

2 |

+0.353 0.4546 |

-32 |

Not improved, irregular |

NO |

No |

- |

||

|

3 |

-0.812 0.0162 |

73 |

Very irregular, improves at the end of therapy phase |

YES, LARGE |

0.545 |

-0.332 0.5012 |

YES |

|

|

8 |

1 |

-0.804 0.0008 |

65 |

Irregular but big improvement during therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.515 |

-0.569 0.1048 |

YES |

|

2 |

-0.749 0.0006 |

68 |

Big improvement in first third of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.578 |

-0.476 0.1590 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.635 0.0082 |

56 |

Irregular but big improvement during therapy and follow up |

YES, MEDIUM |

0,37 |

-0.282 0.4062 |

YES |

|

|

9 |

1 |

-0.958 0.0001 |

78 |

Gradual and big improvement in first third of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.436 |

-0.894 0.0018 |

YES |

|

2 |

-0.951 0.0002 |

78 |

Gradual and big improvement in first third of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.428 |

-0.866 0.0046 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.981 0.0001 |

88 |

Gradual and big improvement in first third of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.713 |

-0.930 0.0014 |

YES |

|

|

10 |

1 |

-0.854 0.0008 |

71 |

Extremely irregular, but better in follow up |

YES, LARGE |

No |

YES |

|

|

2 |

-0.973 0.0001 |

87 |

Big improvement in beginning of therapy |

YES, LARGE |

0.33 |

-0.923 0.0001 |

YES |

|

|

3 |

-0.982 0.0001 |

85 |

Extremely irregular, but better in follow up |

YES, LARGE |

0.757 |

-0.963 0.0001 |

YES |

|

Tab. 3: Results for research questions I and III

Research question II: Is the change clinically meaningful?

As shown in Table 4, nine of the ten cases showed indicators of meaningful therapeutic change, while patient 2’s results were debatable. In the case of patient 7, two of the three target complaints showed meaningful change.

In patient 2, test for level change and MBLR scores indicated small or medium change in the target complaints, but OQ-45 scores did not drop between baseline and follow up phases. However, the patient started in the «functional» range according to her OQ scores, and Hamilton anxiety scores dropped from moderate (21) to low levels (8) between the baseline and the follow up seven months after the end of the therapy.

In all nine other cases OQ-45 scores showed significant reduction, above the reliable change index minimum of 17. Also, all other patients showed improvement in their anxiety scores (from moderate to low or from severe to low in the case of patient 7) and in their BDI scores (from moderate to minimal, or from low to minimal in patients 6 and 4). For example, patient 3 moved from clinical population to normal population, showed clinically meaningful change index, and moved from moderate anxiety to no anxiety.

In summary, average Hamilton scores started at 22.7 at session 0 and improved to 9.9 at the final session and 8.0 at the 6 months follow up session. Average OQ-45 scores started at 73.5 and improved to 46 at the final session and 46.3 at follow up. BDI scores also improved from 17 at session 0 to 5.6 at the final session and 5.0 at follow up. All together, these results show that in nine of the ten cases the therapeutic change was definitely meaningful and maintained through time, while in the remaining one case there were mixed indicators.

|

Patient nº |

Diagnosis |

Measure |

Session 0 |

Final therapy session |

Follow up session |

Conclusion |

|

1 |

Anxiety disorder |

Hamilton Test |

13 |

3 |

3 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

50 |

9* |

14* |

|||

|

2 |

Generalized anxiety |

Hamilton Test |

21 |

20 |

8 |

DEBATABLE |

|

OQ-45 |

54 |

52 |

57 |

|||

|

3 |

Anxiety disorder |

Hamilton Test |

17 |

10 |

12 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

67 |

39* |

29* |

|||

|

BDI |

13 |

3 |

7 |

|||

|

4 |

OH, agoraphobia, |

Hamilton Test |

19 |

6 |

4 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

62 |

21* |

34* |

|||

|

BDI |

11 |

3 |

2 |

|||

|

5 |

Panic – agoraphobia, generalized anxiety |

Hamilton Test |

29 |

9 |

9 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

90 |

59* |

44* |

|||

|

BDI |

19 |

7 |

4 |

|||

|

6 |

Mixed anxiety and depression |

Hamilton Test |

17 |

6 |

5 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

49 |

40 |

27* |

|||

|

BDI |

11 |

7 |

5 |

|||

|

7 |

Mixed anxiety and depression |

Hamilton Test |

39 |

12 |

8 |

YES (for two of three TC) |

|

OQ-45 |

96 |

76* |

70* |

|||

|

BDI |

21 |

5 |

7 |

|||

|

8 |

Anxiety disorder |

Hamilton Test |

25 |

10 |

8 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

99 |

49* |

42 |

|||

|

BDI |

21 |

7 |

5 |

|||

|

9 |

Adapt dis. with anxiety symptoms |

Hamilton Test |

23 |

10 |

13 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

77 |

41* |

40 |

|||

|

BDI |

23 |

7 |

5 |

|||

|

10 |

Panic without |

Hamilton Test |

24 |

13 |

10 |

YES |

|

OQ-45 |

91 |

59* |

39* |

|||

|

BDI |

21 |

4 |

3 |

Tab. 4: Results for research question II

Research question III: Can the improvement be attributed to the therapy process?

The three-step process detailed in Table 3 was conducted to explore if the change could be attributable to non-therapy downward trend of measurements. After regression analysis, we found that nine TC did not have a statistically significant trend, so we did not calculate their partial correlation. Of the remaining 22 target complaints, we found that in 15 TC the improvement could be attributed to the therapy while controlling for the existing trend influence, with r values of partial correlation ranging from -0.67 to -1, and all p scores below 0.05. In the seven remaining TC a visual analysis was needed.

In five target complaints, visual analysis showed distinct short-term periods of the TC values raising sharply, thus distorting the values of the partial correlation coefficients, but it was not associated with the presence of the trend. Therefore, changes here could be regarded as belonging to the therapy, and not the influence of the trend. In the remaining two TC the results were debatable, as the visual analysis showed the clear short-term trend, ending in the middle of the therapeutic phase (e.g. TC3 of patient 4 considered in detail below). This could be caused by more successful therapy for this target complaint than for the rest TC, or by a fast natural remission. Therefore, to obtain the final answer to the third research question here a qualitative analysis of the therapy process would be required.

Meta-analysis

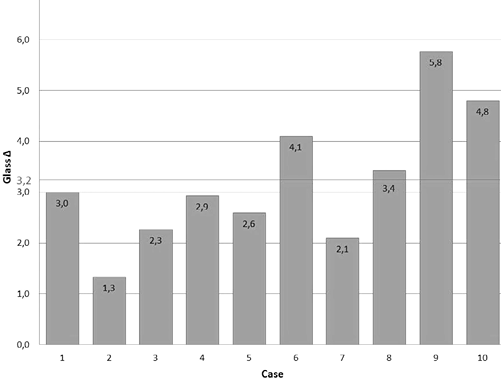

Figure 1 shows that cases 1, 4, 8 have ES values close to the ES value of the whole study, equal to 3,2. Cases 2, 9, 10 are far from it, and therefore require a detailed qualitative analysis.

Fig. 1: Meta-Analysis of all 10 cases

Detailed analysis of case No. 4: «Clara»

An example of the more detailed results that can be obtained using this methodology is presented in case No. 4, chosen because its TC focus mainly on anxiety and because its Glass’ Δ value of 2.9 place it close to the mean of the whole study.

Clara was a 26 y/o woman, kinesiologist, single, living with her mother and two brothers. The therapist was a 33 y/o male, in his third year of Gestalt training, with six years’ experience as a psychotherapist. The MINI psychiatric interview conducted by the therapist indicated a clinical diagnosis of agoraphobia, recurrent depressive disorder and alcohol abuse. She also showed mild depression and moderate anxiety (BDI-1=11; Hamilton=19). The OQ-45 categorized her in the functional range, so despite her diagnosis she could function relatively well.

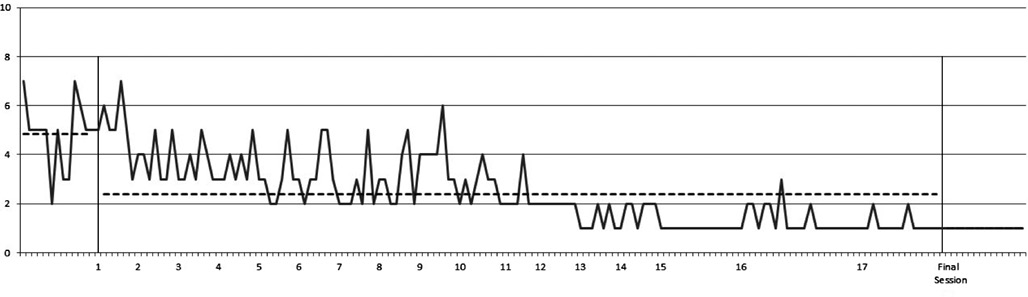

Visual analysis shows that the averages of all TC (red dotted lines in the graphs in figures 2,3,4) have improved noticeably during three phases. This corresponds to the high ES obtained in the form of a Pearson correlation coefficient calculated by SMA for all three TCs: r from -0.881 to -0.939, which indicates a close relationship between the decrease in TC values and whether they were measured before or after therapy. In addition, high values have ES in the form of MBLR: from 74 % to 79 %, which indicates a 75 % reduction in the level of patient complaints compared to that observed prior to therapy.

Fig. 2: Target Complaint n°1 during all three phases («I’m not sufficient to my family.«)

Fig. 3: Target Complaint n°2 during all three phases («I’m desperate when idle.«)

Fig. 4: Target Complaint n°3 during all three phases («I feel frequently anguished.«)

Visual analysis also shows that the variation rose steeply in the middle of therapy for TC1 and in the first half of therapeutic phase for TC2 and becomes minimal for all TC after the 12–13 session. The presence of a downtrend is also noticeable on all three graphs, which is confirmed by the values of the R-square coefficient for the corresponding regression: from 0.574 to 0.653.

The graph for TC3 shows that the measurement changes from the initial phase to the subsequent phases are close enough to this trend, which shows an example of the need for an answer here to the third research question. Since the partial correlation coefficient in the SMA was insignificant (p=0,1614), there is reason to state that the reduction of the TC is due to the influence of the trend. However, visual analysis shows the similar pattern of high variation during baseline and the first part of therapy, and a noticeable improvement after session 7. This improvement became stable after session 12 and continued in the follow up session nine months later, when Clara rated her TC3 with an average score of 1 for the last week. This visual analysis suggests that the changes were not a product of the patient’s natural remission, but until a more detailed qualitative analysis, attribution of these changes to the therapy remains debatable.

The evidence of Clara’s improvement in therapy is proved not only by the dynamics of her target complaints, but also the normalization of anxiety and depression indicators (Hamilton = 6 in the final session and 4 on follow up session, BDI = 3 and 2, respectively).

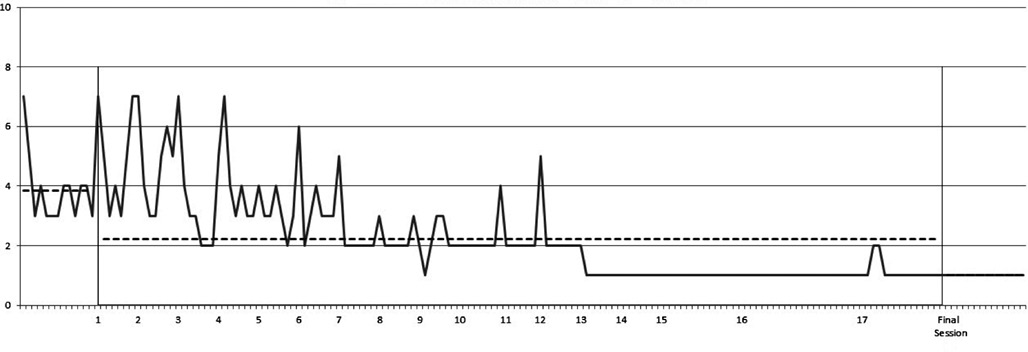

In this case, OQ-45 data were collected not only at the beginning and at the conclusion of the study, but also at each session. In the next graph (figure 5), we see the evolution of Clara’s general distress. OQ-45 increased sharply after the first session (from 62 at session 0 to 102 before session 2) and then moved down to lower than initial levels (50 before session 4). After that, a gradual and steady decrease in distress scores appeared after session 13 until session 17 (from 48 before session 13 to 20 before session 17).

Taken together, the fluctuation of these scores show turning points during the therapy phase, indicating important psychotherapeutic moments than will be explored in a future qualitative analysis focused on understanding the change mechanisms that explain the symptomatic improvement.

Fig. 5: OQ-45 scores during all three phases (OQ Total; symptoms; Interpersonal; Social Role; final session; follow up session)

Discussion

Results of the study. Evidence of the efficacy of Gestalt therapy was confirmed in several ways in this study: As shown on Table 5 below, in almost all the TC we saw pre-post change; in almost all cases there were clear indicators that the change was clinically meaningful, and in almost all TCs change was attributable to therapy. The reliable, statistically significant results obtained in our study suggest that Gestalt therapy (GT) can be a viable alternative to other effective approaches, contradicting previous findings about the relative inefficacy of humanistic-experiential (HE) therapies with this population (Angus et al., 2015; Lambert, 2013).

|

Patient |

Pre post change? |

Clinically meaningful? |

Attributable to therapy? |

|

1 |

Yes, Large |

Yes |

Yes (TC 1,2,3) & Debatable (TC 4) |

|

2 |

Yes, Small |

Debatable |

Yes |

|

3 |

Yes, Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

|

4 |

Yes, Large |

Yes |

Yes (TC 2,3) & Debatable (TC 1) |

|

5 |

Yes, Large |

Yes |

Yes |

|

6 |

Yes, Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

|

7 |

Yes, Large (TC 1,3) & |

Yes |

Yes (TC 2,3) & Debatable (TC 1) |

|

8 |

Yes, Large |

Yes |

Yes |

|

9 |

Yes, Large |

Yes |

Yes |

|

10 |

Yes, Large |

Yes |

Yes |

Tab. 5: Summary of Results

It is not easy to interpret our results within the HE therapies, since this group of approaches is far from being homogenous. Theoretically, the person-centered approach (PCA), a traditionally prominent approach in this group, does not share the active-directive component with Gestalt therapy. GT actively encourages clients to face their fears and supports them to stay with their anxiety to discover their unwanted emotional schemas. It also uses role-playing to facilitate clients to resolve their needs, improving their coping mechanisms and life skills. Facing unwanted and feared internal stimuli facilitates emotional corrective experiences. The client in GT learns that he/she is able to cope and survive the feared stimuli. It also prevents avoidance responses. In summary, GT integrates active elements that are not present in PCA and some other HE modalities. These elements include exposure, avoidance prevention and skills training as used in CBT.

On the other hand, Emotional Focused Therapy (EFT), the best research-grounded approach among the HE therapies, shares the active-directive component with GT and was developed on the bases of GT interventions (Greenberg, 1983). Unlike EFT, GT puts a strong emphasis on the work with the dynamics of the therapeutic relationship in the here and now. Current GT seems to include elements of Roger’s PCA (humanistic values) and EFT (active transformational interventions) and specifically adds the dialogical here-and-now meeting and the holistic (including body work) elements. In summary, similar mechanisms of change proposed by emotional processing theory, the inhibitory learning model and acceptance-focused therapy can be used to explain the change process in GT (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Craske et al., 2014). All these models converge on the concept of «corrective emotional experience» and «memory reconsolidation process», in which exposure and specially emotional activation of implicit learnings is a key change mechanism (Ecker et al., 2012). Further research is needed to understand the role and therapeutic uses of exposure, specially the differences between its understanding in CBT and humanistic theories. This will shed some light on the specificity of GT and its specific indications for groups of patients who could profit from GT.

Although our results relate mainly to the comparison of the two phases Baseline and Follow up, we considered the dynamics of TC throughout the three phases of the study. With the visual analysis of virtually all TC, there is a consistent improvement in the course of therapy: in some cases continuous (2, 3, 6), in some cases irregular (4, 5, 7, 8, 10), and in some cases a mixture of both types, for different TC. Further qualitative and quantitative process research will help us understand and differentiate these mechanisms better. In the course of the study, a vast amount of qualitative data about the therapeutic phase was collected, including therapist’s journal and audio/video recording of all sessions. In the future, we will combine the quantitative results with a qualitative analysis of the data obtained in our study. Another option for future studies would be to collect process data regarding potential change mechanisms (e.g. Interventions to contact previously disowned feelings and desires) and perform mediation analysis. All this will allow results to be clarified and explained, the specific factors of GT approach to anxiety to be identified and the internal and external validity of the study to be strengthened.

Design of the study. Despite the recent popularity of N-of-1 trials in healthcare (Mengersen et al., 2011; Punja et al., 2016), there are threats to their internal and external validity that need to be addressed (Horner et al., 2005). Instrumentation and testing confounds were removed by using reliable, well-proven instruments. Performance bias and maturation threats were studied in detail by working on the third research question, excluding natural remission. Other non-therapy factors affecting the outcome, including the history confound, are expected to be detected in the future using a therapeutic journal. The most difficult threat for experimental control is the selection bias, as it is possible that the clients that volunteered to be a part of the study share special characteristics (e.g. high conscientiousness) that need to be considered in order to interpret findings correctly. The attrition threat is also relevant and we have instructed all therapists that participate in the study to report when they have clients that have not completed the treatment or have dropped out early.

The external validity of this study is high, because the cases included cover a significant number of anxiety symptoms and comorbidities. SCTS design meets the requirements in both kinds of external validity: generalizability across situations due to the direct applicability of the results of the study in real-life situations of psychotherapy, and; generalizability across people to the extent of the representation of all patients with a diagnosis of anxiety in general. Additional benefit of using SCTS design is approximation of the real-world therapy process, which is included in the scope of ecological validity. Ecological validity is presented in our research naturally, unlike the RCT, where it is difficult to achieve.

Our data analysis strategy considers virtually all the suggestions of the quality standards: the use of both visual and statistical analysis; accounting of autocorrelation; the complementation of target complaints with standard outcome measures; controlling for the existence of non-therapy-related trends; and meta-analysis (Borckardt & Nash, 2014; Borckardt et al., 2008; Kratochwill et al., 2013; Tate et al.; 2013; Wendt & Miller, 2012). However, the use of Glass’ Δ for a future meta-analysis has limitations, as its interpretation is obvious only for normally distributed data (e.g. Case 3) and gives inadequate values when the baseline TC values show little or no variation. Additionally, the use of SMA to control for non-therapy-related trends was not entirely satisfactory. This software’s limitation of <30 data points per phase meant that the trend was only controlled for the baseline and follow up phases and not the longer therapy phase, which could lead to distortions in the calculations. In the future, it makes sense to use the package R instead of SMA to answer the third research question.

Limits and suggestions for further research. Several limitations of our study and subsequent implications for further research need to be mentioned here: (1) There were clients with different kinds of anxiety disturbances in our sample. Although it corresponds with the real daily practice situation and so with the intentions of practice-oriented research, a more differentiated sample selection would allow closer exploration of the mechanisms of change when using GT with specific anxiety symptoms. (2) A GT fidelity scale, which is now being developed with the shared effort of the GT international community (Fogarty et al., 2016), was not yet available at the time of our study. The treatment fidelity was ensured by other ways in our study, but for future research the GT fidelity scale will be the first choice. (3) The therapists were graduate students of one institute with few years of clinical practice, which presents a limitation for the external validity of our study. (4) The correct formulation of the TC at the «session 0» is of extreme importance. An example of the negative consequences of an error is TC2 for patient 7 «I cannot tolerate the abuse in my workplace», which failed to show clinical improvement, as one could question if this was really an ecological therapeutic goal. The worsening of this TC could mean that the patient no longer puts up with abuse and protects herself, or it could mean that she is less able to tolerate the abuse and thus more distressed by it. To clarify these and other possible interpretations, therapists involved in such a study would need more training in this specific skill of formulating TC. (5) There was incomplete data on people that considered going to therapy but did not volunteer for the study, which relates to the aforementioned selection and attrition biases.

Implications for further research projects include two main strategies: broadening the project and including both process and qualitative research findings into a more complex research design. The project can be broadened in several ways: (1) Therapists with different length of practice should be included. (2) Using the advantage of the already established GT research network, cases obtained by this method from different countries can be included, which would expand and enrich the meta-analysis. (3) Various design options and alternative instruments can be used while keeping the basic SCTS design, e. g. replacing OQ-45 with CORE-OM. (4) The SCTS design can be used for GT work with other diagnoses, e. g. for depression. (5) The client’s constant tracking of TC can be explored as an awareness promoting intervention.

SCTS can be useful not only for outcome research. In this paper we focused on efficacy results and quantitative methods. However, as briefly shown in our in-depth case analysis, SCTS provides detailed and continuous change process information. Conducting qualitative analysis and especially exploring the mechanisms of change can supplement the results. Analysis of video-recorded sessions and client follow up interviews would allow us to compare the best and worst sessions, turning points during the therapy process and explore how change occurred (especially regarding anxiety symptoms) in these cases. Qualitative observation would allow us to identify specific processes of change and related GT interventions in the different cases and to compare them with CBT and HE approaches. Gathering data from unsuccessful cases may assist in identifying limits of GT when working with anxiety. Moreover, there are also implications for psychotherapy practice, since SCTS can be useful for implementing feedback-informed treatment and as a learning and supervision tool for novice therapists.

Practical consequences of this study lay not only in suggesting another kind of effective psychotherapy approach to clients with anxiety problems, but also in the possibility of using the proposed research design for psychotherapy efficacy studies in private practice settings with different groups of patients. SCTS designs can be used as a valuable alternative to RCTs, especially in naturalistic outcome studies with clear advantages for studying the processes of therapeutic change in practice-based research networks.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues Jörg Bergmann, Otto Glänzer, Stefan Pfleiderer, Vincent Beja and Tomas Rihacek for their help in different phases of this study.

References

American Psychological Association [APA] (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271–285 (http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271).

Angus, L., Watson, J.C., Elliott, R., Schneider, K. & Timulak, L. (2015). Humanistic psychotherapy research 1990–2015: From methodological innovation to evidence-supported treatment outcomes and beyond. Psychotherapy Research, 25(3), 330–347 (http://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.989290).

Battle, C.C., Imber, S. D. & Hoehn-Saric, R. (1966). Target complaints as criteria of improvement. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 20(1), 184–192.

Beck, A. T. (1978). Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio/TX: Harcourt Brace Jocanocich.

Beretvas, S. N. & Chung, H. (2008). A review of meta-analyses of single-subject experimental designs: Methodological issues and practice. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 2, 129-141 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17489530802446302).

Borckardt, J. J. & Nash, M. R. (2014). Simulation modelling analysis for small sets of single-subject data collected over time. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(3–4), 492–506 (http://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2014.895390).

Borckardt, J.J., Nash, M.R., Murphy, M.D., Moore, M., Shaw, D. & O’Neil, P. (2008). Clinical practice as natural laboratory for psychotherapy research: a guide to case-based time-series analysis. The American Psychologist, 63(2), 77–95 (http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.77).

Campbell, J. M. (2003). Efficacy of behavioral interventions for reducing problem behavior in persons with autism: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 24, 120–138.

Carey, T. A. & Stiles, W. B. (2015). Some Problems with Randomized Controlled Trials and Some Viable Alternatives. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(1), 87–95 (http://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1942).

Ceballos, D. (2014). Trastorno De Ansiedad Generalizada. Figura Fondo, 36, 1–13.

Chambless, D.L., Baker, M.J., Baucom, D.H., Beutler, L.E., Calhoun, K.S., Crits-Christoph, P., … Woody, S. (1998). Update on empirically validated therapies, II. Clinical Psychologist, 51(1), 3–16.

Chambless, D. L. & Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 7–18.

Chambless, D. L. & Ollendick, T. H. (2001). Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 685–716.

Craske, M.G., Treanor, M., Conway, C.C., Zbozinek, T. & Vervliet, B. (2014). Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23 (http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006).

Deane, F.P., Spicer, J. & Todd, D. M. (1997). Validity of a Simplified Target Complaints Measure. Assessment, 4(2), 119–130 (http://doi.org/10.1177/107319119700400202).

Ecker, B., Ticic, R. & Hulley, L. (2012). Unlocking the Emotional Brain. London: Routledge.

Elliot, R. (2003) CSEP-II Experiential Therapy Session Form. Toledo/OH: University of Toledo Department of Psychology.

Elliott, R. (2013). Person-centered/experiential psychotherapy for anxiety difficulties: Theory, research and practice. Person-Centered &

Experiential Psychotherapies, 12(1), 16–32 (http://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2013.767750).

Elliott, R., Greenberg, L.S., Watson, J.C., Timulak, L. & Freire, E. (2013). Research on Humanistic- Experiential Psychotherapies. In M. Lambert (Hrsg.), Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (S. 495–538). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Foa, E. B. & Kozak, M. J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 20–35.

Fogarty, M., Bhar, S., Theiler, S. & O’Shea, L. (2016) What do Gestalt therapists do in the clinic? The expert consensus. British Gestalt Journal, 25(1), 32–41.

Folke, F., Hursti, T., Tungström, S., Söderberg, P., Kanter, J.W., Kuutmann, K., … Ekselius, L. (2015). Behavioral activation in acute inpatient psychiatry: a multiple baseline evaluation. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 46, 170–181 (http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.10.006).

Francesetti, G., Gecele, M. & Roubal, J. (Hrsg.). (2013). Gestalt therapy in clinical practice: From psychopathology to the aesthetics of contact. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

Glass, G.V., McGaw, B. & Smith, M. L. (1981). Meta-analysis in social research. Beverly Hills/CA: Sage.

Greenberg, L. S. (1983). Toward a task analysis of conflict resolution in Gestalt intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 20(2), 190–201.

Hamilton, M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32(1), 50–55.

Hague, B., Scott, S. & Kellett, S. (2015) Transdiagnostic CBT Treatment of Co-morbid Anxiety and Depression in an Older Adult: Single Case Experimental Design. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(1), 119–124.

Herrera, P. (2016). The construction of a gestalt-coherent outcome measure. In J. Roubal, P. Brownell, G. Francesetti, J. Melnick & J. Zeleskov-Djoric (Hrsg.), Towards a Research Tradition in Gestalt Therapy (S. 1–368). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Hollon, S. D. & Beck, A. (2013). Cognitive and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies. In M. Lambert (Hrsg.), Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (S. 393–442). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Horner, R.H., Carr, E.G., Halle, J., Mcgee, G., Odom, S. & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165–179.

Kratochwill, T. R. & Levin, J. R. (2010). Enhancing the scientific credibility of single-case intervention research: Randomization to the rescue. Psychological Methods, 15(2), 124–144 (http://doi.org/10.1037/a0017736).

Kratochwill, T.R., Hitchcock, J.H., Horner, R.H., Levin, J.R., Odom, S.L., Rindskopf, D. M. & Shadish, W. R. (2013). Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial and Special Education, 34, 26–38.

Lambert, M. (2013). Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. John Wiley & Sons.

Lambert, M., Burlingame, G., Umphress, V., Hansen, N., Verneersch, D. & Clouse, G. (1996) The Reliability and Validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 3, 106–116.

Manolov, R. & Solanas, A. (2008). Comparing N = 1 effect sizes in presence of autocorrelation. Behavior Modification, 32, 860–875 (http://doi.org/10.1177/0145445508318866).

Manolov, R., Guilera, G. & Sierra, V. (2014) Weighting strategies in the meta-analysis of single-case studies. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 1152 (https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0440-0).

Mengersen, K., McGree, J. M. & Schmid, C. H. (2015) Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Using N-of-1 Trials. In J. Nikles & G. Mitchell (Hrsg.) The Essential Guide to N-of-1 Trials in Health. Dordrecht: Springer (https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94).

Olive, M. L. & Smith, B. W. (2005). Effect size calculations and single subject designs. Educational Psychology, 25(2-3), 313–324 (http://doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000301238).

Perls, F. S. (1969). Gestalt Therapy Verbatim. New York: Bantam Books.

Punja, S., Bukutu, C., Shamseer, L., Sampson, M., Hartling, L., Urichuk, L. & Vohra, S. (2016). N-of-1 trials are a tapestry of heterogeneity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 76, 47–56.

Robine, J. M. (2013). Anxiety Within the Situation: Disturbances of Gestalt Construction. In G. Francesetti, M. Gecele & J. Roubal (Hrsg.), Gestalt Therapy in Clinical Practice. From Psychopathology to the Aesthetics of Contact (S. 479–495). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Roth, A. & Fonagy, P. (2013). What Works for Whom? Second Edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Roubal, J., Gecela, M. & Francesetti, G. (2013). Gestalt Therapy Approach to Diagnosis. In G. Francesetti, M. Gecele & J. Roubal (Hrsg.), Gestalt Therapy in Clinical Practice. From Psychopathology to the Aesthetics of Contact (S. 79–106). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Shahar, B., Bar-Kalifa, E. & Alon, E. (2017). Emotion-Focused Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder: Results from a Multiple-Baseline Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(3), 238–249 (http://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000166).

Sheehan, D., Lecrubier, Y., Harnett-Sheehan, K., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R. & Dunbar, G. (1998). The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–23.

Silberschatz, G. (2017). Improving the yield of psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy Research, 27(1), 1–13 (http://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1076202).

Smith, J. D. (2012). Single-case experimental designs: A systematic review of published research and current standards. Psychological Methods, 17(4), 510–550 (http://doi.org/10.1037/a0029312).

Smith, J.D., Borckardt, J. J. & Nash, M. R. (2012). Inferential Precision in Single-Case Time-Series Data Streams: How Well Does the EM Procedure Perform When Missing Observations Occur in Autocorrelated Data? Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 679–685.

Tate, R.L., Perdices, M., Rosenkoetter, U., Wakim, D., Godbee, K., Togher, L. & McDonald, S. (2013). Revision of a method quality rating scale for single-case experimental designs and n-of-1 trials: The 15-item Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) Scale. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 23(5), 619–638 (http://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2013.824383).

Timulak, L., McElvaney, J., Keogh, D., Martin, E., Clare, P., Chepukova, E. & Greenberg, L. (2017). Emotion-Focused therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: An exploratory study. Psychotherapy, 54(4), 361–366.

Tschuschke, V., Crameri, A., Koemeda, M., Schulthess, P., Von Wyl, A. & Weber, R. (2010). Fundamental reflections on Psychotherapy research and Initial results of the naturalistic Psychotherapy Study on outpatient treatment in Switzerland (PaP-S). International Journal of Psychotherapy, 14(3), 23–35.

von Bergen, A. & de la Parra, G. (2002). OQ-45.2, Cuestionario para evaluación de resultados y evolución en psicoterapia: adaptación, validación e indicaciones para su aplicación e interpretación [OQ-45.2, an outcome questionnaire for monitoring change in psychotherapy: adaptation, validation and indications for its application and interpretation]. Terapia Psicológica, 20(2), 162–176.

Watson, J. & Greenberg, L. (2017) Emotion-Focused Therapy for Generalized Anxiety. Washington: APA Books.

Wendt, O. & Miller, B. (2012). Quality Appraisal of Single-Subject Experimental Designs: An Overview and Comparison of Different Appraisal Tools. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(2), 235–268.

Whalon, K.J., Conroy, M.A., Martinez, J. R. & Werch, B. J. (2015). School-Based Peer-Related Social Competence Interventions for

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis and Descriptive Review of Single Case Research Design Studies. J Autism Dev Disord, 45, 1513 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2373-1).

The Authors

Pablo Herrera – Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile

Illia Mstibovskyi – Southern Regional Gestalt Institute, Rostov-on-Don, Russia

Jan Roubal – Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Science, Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Philip Brownell – Portland Gestalt Therapy Training Institute, Portland/Oregon, USA

The authors are researchers, psychotherapists and trainers of Gestalt therapy. They are coordinators of the international practice-based research network of the Single-Case Time Series project.

Contact

Pablo Herrera Salinas

Escuela de Psicología

Universidad de Chile

E-Mail: pabloherreras@uchile.cl