Psychotherapy regulation in European countries

Towards psychotherapy as an autonomous profession and scientific discipline

Miran Možina

Psychotherapie-Wissenschaft 14 (2) 2024 93–100

www.psychotherapie-wissenschaft.info

https://doi.org/10.30820/1664-9583-2024-2-93

Abstract: In recent decades, two processes have been crucial for the development of psychotherapy regulation, which are interlinked and mutually reinforcing: efforts to legalise psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, and efforts to academise psychotherapy as an autonomous scientific discipline. While in Europe the European Association for Psychotherapy (EAP) plays a key role in efforts to legalise psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, the academisation of psychotherapy in the twentieth century started at postgraduate level, then, after the Bologna reform, at Masters and Doctoral level and, since 2005 also at undergraduate level, first in Austria and then in Slovenia and Germany. Based on brief descriptions of the regulation of psychotherapy in some European countries – Germany, Sweden, Finland, Austria, Malta and Croatia – it is pointed out that concern for equitable access to psychotherapy and its quality for those in need of such kind of help must be a key criterion and goal in efforts to regulate psychotherapy. The international comparison also shows that psychotherapy will survive but not flourish if it remains only in the hands of doctors and psychologists as a method or specialisation.

Keywords: psychotherapy regulation, Strasbourg declaration, academisation, psychiatry, psychology, mental health

Introduction

I started my active collaboration for a Slovenian law on psychotherapy in 2004 and participated already in three working group at the Ministry of Health (the last one in 2023). The main reason are the disagreements between psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, on the one hand, and professional psychotherapists (where I am also involved), on the other. The former advocate psychotherapy as a method of work that only they should practice, while the latter advocate psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, which needs an academic educational path, a professional chamber with compulsory membership and the integration of psychotherapists into a number of sectors, not only health, but also social welfare, education, justice, home affairs, the economy, sport, health tourism, etc. (Možina 2023).

Unfortunately, Slovenia is only one of the most European countries where psychiatrists (doctors) and (clinical) psychologists have successfully prevented psychotherapy from being regulated as an autonomous profession, or are trying to keep the title of psychotherapist or psychotherapy activity to themselves (e. g. Italy, Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Belgium, France, Denmark, Latvia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Kosovo, Romania (Hunt et al. 2021). This has been demonstrated in the most dramatic way so far in the Netherlands and Belgium.

After psychotherapy had been regulated as an autonomous profession in the Netherlands since 1986, it was abolished in 2001 by the Minister of Health, who reserved the title of psychotherapist for psychiatrists and clinical psychologists only. Refusing to engage in dialogue with psychotherapists, who were severely harmed by the new undemocratic decisions of the Ministry, they immediately organised themselves effectively and regained their rights. In 2005, the Ministry of Health re-introduced the Register of Psychotherapists, and health professionals who are not psychiatrists or psychologists could again obtain the title of psychotherapist if they have completed the relevant training (van Broeck & Lietaer 2008).

Belgian psychotherapists also succeeded, after years of efforts, in getting a law on psychotherapy as an autonomous profession passed by Parliament in April 2014, to come into force by September 2016 at the latest. However, in May 2015, when almost all the necessary documents for implementation had been prepared, a new version of the law proposed by the Minister of Health and Social Affairs was unexpectedly adopted. It no longer defined psychotherapy as a autonomous profession, but only as a method that can only be practiced by clinical psychologists, special educators and doctors with completed psychotherapy training. Despite an appeal to the Supreme Court, Belgian psychotherapists have only been able to mitigate some of the damage and fight for an autonomous profession to this day (Sasse & Vrancken 2014, 2017; Mistiaen et al. 2019).

Despite the dominance of medicine and psychology in regulating psychotherapy, it is gratifying and hopeful that the European Commission in its European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO) project, defined psychotherapist as independent occupation from psychology, psychiatry, and counselling (European Commission 2017).

Psychotherapy as an autonomous profession and scientific discipline

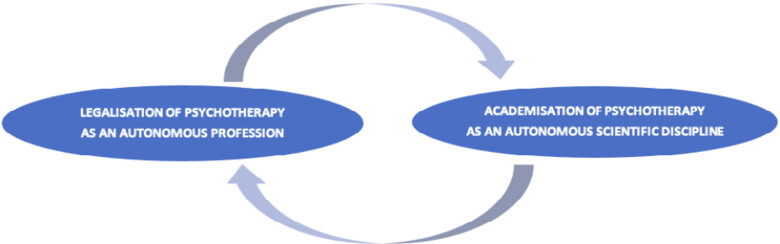

In recent decades, two processes have been crucial for the development of psychotherapy regulation, which are interlinked and mutually reinforcing: efforts to legalise psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, and efforts to academise psychotherapy as an autonomous scientific discipline (Fig. 1). While professional development is mainly linked to clinical practice, scientific development is mainly linked to research. While legalisation is linked to the profession and needs a specific law, academic education is linked to higher education legislation. The «scientist-practitioner model» (Jones & Mehr 2007), which has been gaining ground in psychotherapy over the last decades, is an attempt to bridge or circularly reinforce both development processes.

Fig. 1: Efforts to legalise psychotherapy as an autonomous profession are linked to and reinforce each other in a circular way with efforts to academise psychotherapy as an autonomous scientific discipline.

In Europe, European Association for Psychotherapy (EAP) plays a key role in efforts to establish psychotherapy as an autonomous profession (Hunt 2020), but is for many years facing strong opposition from two European associations for psychologists and psychiatrists: European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations (EFPA) and European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) European Board of Psychiatry (EFPA & UEMS, 2009), which oppose the idea of psychotherapy as an autonomous profession. At the same time it is interesting that the cross-sectional European study has shown the need for improved psychotherapy training for European psychiatrists (Gargot et al. 2017).

The academisation of psychotherapy towards an autonomous scientific discipline in Europe in the twentieth century started at postgraduate level, then, after the Bologna reform, at Masters and Doctoral level and, in since 2005, also at undergraduate level. The first university in the world to open the possibility of a direct 5-year psychotherapy course (3-year bachelor and 2-year master) immediately after the matura was Sigmund Freud University in Vienna in 2005 (Pritz et al. 2020), followed by its branch in Ljubljana (SFU Ljubljana) in 2006 (Možina 2007). In 2019, a new law in Germany has made academic training in psychotherapy after matura the only education path. Austria adopted a similar regulation with the psychotherapy law amendment in April 2024. Austria and Germany are therefore currently the only countries in the world with academic training for psychotherapy as a first profession.

Despite the EAP’s major contribution to the evolution of psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, the EAP’s recognition of the academic study of psychotherapy directly after the high school (matura) was not so easy. Many EAP members had a negative or ambivalent attitude towards this possibility of psychotherapy training which was established at the Sigmund Freud University in 2005 (Pritz 2011; Možina 2023). It wasn’t until 2017 that the EAP finally acknowledged that SFU graduates with master’s degrees could directly apply for the European Certificate of Psychotherapy (ECP). It took 12 years to this acceptance despite the fact that SFU’s academic standards of education surpassed those of the ECP in both quantity and quality demands. With this recognition the fifth point of the Strasbourg Declaration on Psychotherapy (EAP, 1990), which many EAP members interpreted as implying that psychotherapist training was only viable and sensible as a second profession, has been revised.

Since Germany is the only country in the world where the new psychotherapy law in 2019 opened direct route to post-secondary education for psychotherapy, which means that psychotherapy can also be a first profession, the German amendment is set out in more detail below. This is followed by short summaries psychotherapy regulations in Sweden, Finland, Austria, Malta and Croatia which are relatively positive examples of psychotherapy professional autonomy.

Germany: a new training pathway for the autonomous profession of psychotherapist

On 26 September 2019, the German Federal Parliament passed the new Psychotherapeutic Therapy Act (Psychotherapeutengesetz, abbreviated PsychThG; Bundesministerium der Justiz 2024), which entered into force on 1 September 2020. A key innovation is the creation of a new education pathway:

- a three-year undergraduate course, which can be polyvalent or exclusively psychotherapy-oriented;

- a two-year master’s degree in a chosen psychotherapeutic approach;

- a professional examination after the master’s degree, the title «psychotherapist» and a license to practice psychotherapy;

- five years of further training in hospitals, outpatient clinics and prevention programmes, which, once completed, leads to the qualification of «specialist psychotherapist» and a license to provide psychotherapeutic services in the public health system.

The previous Psychotherapy Act of 1999 distinguished between medical and psychological psychotherapy and introduced two new professions – psychological psychotherapist and child and adolescent psychotherapist. This law was a particular success for psychologists, who fought for it for almost twenty years. Psychological psychotherapists were able to work autonomously within the health system and were licensed and concessioned by health insurance companies. In 2003, the Chamber of Psychotherapists was also founded, which today represents the interests of some 59.000 members.1

The uniform national designation of the profession as «psychotherapist» introduced by the new law has removed the previous addition of «psychological», indicating a move away from psychology as a basic science. The new law has given the profession of psychotherapist a new legal basis, broadening its competences, recognised and upgraded their autonomy, so that psychotherapists have now become, in terms of their status equivalent to doctors.

Germany is the only country in the world, which by law introduced psychotherapy training for the first profession with a five-year post-secondary diploma course, which is divided into a three-year undergraduate programme and a two-year master’s program under the Bologna system. It culminates in a professional examination («Approbation» in German) and the award of a license, i. e. a permit to practice as a psychotherapist.

Different academic fields and higher education institutions are currently in the process of adapting to the new Regulations on the Licensing of Psychotherapists, and a whole range of possible innovations is opening up: From minimal adjustments to the study content of existing psychology courses (with a move away from academic psychology, related fields of application and previous employment opportunities for psychotherapists), through the establishment of psychotherapy in public medical, humanities and social sciences faculties or private universities, to the establishment of independent faculties of psychotherapy. These educational institutions must ensure that all scientifically recognised psychotherapeutic approaches can be taught to a comparable extent. If higher education institutions cannot themselves guarantee these requirements, particularly for practical training, they may cooperate with other relevant institutions.

After obtaining the license, the psychotherapist enters a five-year further training (in German «Psychotherapeut in Weiterbildung») in the psychotherapeutic approach chosen during the master’s degree. During this period, he/she becomes entitled to provide psychotherapy in inpatient treatment settings (e. g. hospitals, day hospitals), outpatient clinics and preventive programmes which are part of the German public health insurance system (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung or GKV System). His official title in the GKV system is «assistant psychotherapist» («Assistenzpsychotherapeut»). This means that he no longer has the status of a student, but is a full-time employee with all the rights that go with it.

State-recognised training institutes (or societies), which were previously private, are to be transformed into further education institutes, and their teaching clinics are to be integrated more closely into health care system, rather than having a purely educational function. In this way, in the context of continuing training, psychotherapy training institutions could take a leading role in the supervision of the outpatient part of education and be integrated into the public outpatient psychotherapy network within the public health system.

After successfully completing a five-year training course, a psychotherapist can use the title «specialist psychotherapist» («Fachpsychotherapeut») and to enter in the registers which, until the introduction of the new law, were kept by each German state only for licensed doctors (i. e. their services are paid for by insurance companies). Any specialist psychotherapist will therefore be able to apply to the Landes Association of licensed doctors (Kassenärztliche Vereinigung des Landes; KV) for a license to provide psychotherapy services independently in the context of public health care.

It is important to note that the new law has not interfered with well established psychotherapy specialisations in medicine. Since 1992, German doctors have introduced a new group of specialists, doctors of psychotherapeutic medicine, and psychotherapy became a compulsory part of specialisation in psychiatry. This led to the creation of new specialist profiles: specialist in psychiatry and psychotherapy and specialist in child/adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy. Psychotherapeutic medicine became one of specialisations, like psychiatry, dermatology, internal medicine, orthopaedics etc. This has led not only to a new postgraduate specialisation, but also to a new field in the public health system. All psychotherapy specialisation require five years of postgraduate training, three of which must be spent in hospital. All doctors wishing to practice psychotherapy have to complete a three-year programme in psychotherapy, one year of which takes place in the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, in addition to their specialisation, e. g. in general medicine, internal medicine, etc. Under the new law medical psychotherapists and specialists in psychosomatic medicine and psychotherapy may also choose to use the professional title «psychotherapist», but may also use the title «medical psychotherapist» («Ärztlicher Psychotherapeut»).

So Germany is the only country in the world where my dreams of psychotherapy as an autonomous profession and direct academic study has come true, although the previous law of 1999 was most favourable to psychologists and faculties with psychology degree programmes still have a distinct advantage in the current situation. However, the direct route to post-secondary education for psychotherapy is open, which means that psychotherapy can also be a first profession and new academic first- and second-level psychotherapy degree programmes may also be created.

Sweden: the first in Europe to pass the law on psychotherapy

The procedure of issuing licenses for all psychotherapeutic modalities was granted by the government in 1985 after the decision of the parliament that psychotherapy was an autonomous profession. Psychotherapeutic training consists of three steps (Grebo & Elmquist 2002): (1) basic three-year programme, which is available to candidates who finished secondary school and it ends with the Bachelor’s degree. This stage is included in the training to become a psychologist, but other professions such as general practitioners, medical nurses and social workers, can apply to undertake this training. Beside theory and personal experience a candidate on this stage can perform psychotherapy under supervision. Most of them work in hospitals or institutes for patients with special needs; (2) specialized training in psychotherapy. Psychiatrists and psychologists can directly enter this stage. Specialists of other professions e. g. social workers, dental practitioners, general physicians, nurses, theologists etc. are required to complete stage one beforehand. There is no minimum entry age specified. Specialized education lasts for at least three years with at least 2.000 hours, but most of the candidates complete it in five years and it consists of theory, supervised psychotherapeutic practice and personal experience. It ends with a diploma that enables the candidates to apply for a license. The detailed content of psychotherapy studies is not strictly regulated by law, so the duration, intensity and content may vary slightly from one training provider to another. It is also common for individual trainings to focus on a particular modality within psychotherapy (Johansson & Fahlke 2019, p. 417); (3) stage three enables psychotherapists to be granted the title of supervisor.

An individual who wishes to use the title psychotherapist must obtain a license issued by the National Board of Health and Social Care. The Board register and keep a register of all health and care professionals (HOSP). Supervision of the work of all health and care workers is carried out by The Swedish Inspectorate for Health and Social Care (IVO). The register is open to persons who have trained as a psychotherapist in Sweden or who are qualified to practice as a psychotherapist in one of the other EU Member States. The number of psychotherapists is growing slightly each year: in 2002 there were approx. 4.000 and in 2020 7.666 (Statista 2023).

However, based on the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s regulations on specialist training for physicians (Socialstyrelsen 2015), an education plan for basic psychotherapy training for physicians in psychiatry has been established. Thus, a basic course in psychotherapy, only accessible for physicians, has been offered annually since 2013 (Johansson & Falke, 2019).

Psychotherapy is an integral part of the health care system and is generally practiced at all levels of care, from primary to specialised care. The availability and scope of psychotherapeutic treatment may vary depending on the location in the country. Within a country, there are different systemic solutions to the extent to which psychotherapy provided by psychotherapists in private practice is financed by the Health Care System or by different forms of health insurance (SPR – Sweden).

Finland: how to provide adequate psychotherapeutic service for people from lower social strata

In Finland, there is a law from 1994 that protects the title psychotherapist and regulates the profession of psychotherapist as an independent one (Act Concerning Health Care Professionals No. 559/94 and Decree Concerning Health Care Professionals No. 564/94) (Finlex 2018, 2024). Psychotherapist training programmes are professional continuing education comparable to the continuing education of healthcare professionals. It is only available to candidates who have already completed: (1) an applicable master’s-level degree at a university, or an applicable qualification in health and social services at a university of applied sciences; the degree must include, or the candidate must have otherwise completed, 30 credits of studies in psychology or psychiatry; (2) a post-secondary nursing qualification plus a specialisation in psychiatry if the qualification did not include studies in psychiatry.

Applicants to the programmes are required to have experience in working with clients in the mental health sector or corresponding experience (two or more years), as well as applicable prior education in the healthcare or social care sector. This means that psychotherapy training tends to be multiprofessional, so that it can involve nurses, social workers, theologians, special educators or teachers, in addition to doctors and psychologists. From the beginning of the year 2012 only psychotherapy training programmes arranged by or together with the universities and psychological or psychiatric institutions are accepted. The scope of training must be at least 60 to 80 credits, divided between theoretical studies, supervised clinical psychotherapy with clients, personal psychotherapy and final written project work.

Ministry of Health runs the register of psychotherapists. In 2008, there were 4.500 psychotherapists on the official register (Finland has a population of 5,5 million), although there are even more because not all those who are qualified have the title of psychotherapist (Seikkula 2011).

Rehabilitative psychotherapy aims to support an individual’s employment, staying at work and return to work, but it is not linked to occupational health services (OHS) or other employer measures aiming to maintain employees’ work ability. The SII can compensate rehabilitative psychotherapy for 1 to 3 years with a maximum of 80 sessions per year and 200 sessions in 3 years. The applicant must be aged 16–67 and have a diagnosed mental health problem that threatens work ability (or ability to study). This excludes patients whose likelihood to return to working life is low, as well as retired and adolescents. The need for and suitability of the individual for psychotherapy is evaluated by a psychiatrist. To get into this rehabilitative psychotherapy, a psychiatrist statement and a minimum of three months treatment without sufficient response are needed. This creates a structural delay and a practical bottleneck due to the shortage of psychiatrists. In Finland, with a population of 5,5 million, the SII uses over 100 million euros annually to fund psychotherapy for over 60.000 persons (Saarni et al. 2023).

To supplement SII-funded psychotherapy also hospital districts and municipalities offer psychotherapies, often outsourced to private practitioners. Different vouchers are given to different patient groups according to evidence-based guidelines. The supply of short, structured psychosocial treatments targeted to mild to moderate symptom levels has been very limited. A national First-line Therapies initiative is trying to remedy this by introducing a selection of evidence-based psychosocial interventions into primary care (Saarni et al. 2022). Also the Finnish example therefore illustrates the challenge of regulating psychotherapy in a way that allows equitable access to quality services for all segments of the population.

Austria: long-term positive effects of regulating psychotherapy as an autonomous profession

Since the Austrian law of 1991 defined psychotherapy as an autonomous profession (RIS, 2022) the number of psychotherapists has increased, so that by December 2021 there were 11.070 psychotherapists on the national register, the budget inflow has exponentially increased from € 3.2 million in 1992 to around €100 million in 2021, and access to psychotherapy services has improved (Možina 2022).

Since the adoption of the Act in 1991, academic postgraduate programmes at universities such as those in Graz, Salzburg, Innsbruck, the Danube University in Krems and Vienna have also developed rapidly, and it was only a matter of time before an undergraduate psychotherapy programme opened up at one of them. This happened in October 2005, when some 200 students enrolled in a two-level five-year faculty course in psychotherapeutic science at the private Sigmund Freud University Vienna (SFU) (Pritz et al. 2020; Možina 2023). The number of hours for both levels together has exceeded the minimum requirements of Austrian law. The proportion of supervised psychosocial and psychotherapeutic practice is more than 50 % of the total study content, which means that there is a strong emphasis on practical training. For this reason, the SFU also has a psychotherapy clinic, where students can practice under supervision.

The rapidly evolving academisation of psychotherapy was one of the main reasons why the amendment to the law, which has been passed in the National Council in April 2024, has moved psychotherapy training to public universities (RIS 2024). With the reform, the government wants to make psychotherapy training, which currently costs between 25.000 and 50.000 euros, more easily accessible. From 2026 up to 500 master’s study places per year will be offered regionally throughout Austria (ORF 2024). The main changes introduced by the amendment are:

- instead of the two-year preparatory course (i. e. «propedeutics») and specialist training in psychotherapeutic modality, which lasts three to six years, it is possible to complete a two-year master’s degree in psychotherapy after completing a relevant bachelor’s degree at a university or at a technical college;

- the master’s degree is open to more professions: directly recognized studies are human medicine, psychology, social work, social pedagogy, psychosocial counselling, music therapy, medical technical professions, midwifery, advanced healthcare and nursing. For the recognition of other bachelor’s programmes examination is carried out by the respective university;

- the third part of the training is postgraduate psychotherapeutic specialist training at psychotherapeutic societies of different modalities, during which the candidate can work therapeutically under supervision;

- in the third phase of training, the method-specific specialist training, internships at institutions such as psychotherapeutic care facilities and teaching practices, clinics or rehabilitation facilities is mandatory so that the therapists see numerous different psychiatric illnesses during their training;

- direct recognition is possible for: psychotherapists, music therapists, clinical and health psychologists, specialists in psychiatry and psychotherapeutic medicine, specialists in child and adolescent psychiatry, general practitioners with an ÖÄK diploma in psychotherapeutic medicine (PSY I, II and III), specialists of psychosomatic medicine and ÖÄK diplomats in psychotherapeutic medicine (PSY III);

- the professional profile and areas of expertise in psychotherapy: the protection of activities and reserved areas of activity are clearly described and anchored in it – from patient treatment, including psychotherapeutic diagnostics and assessment, to prevention and health promotion, to counselling, care and support for people of all ages and the treatment of patients with severe mental disorders;

- transitional regulations: from 1 January 2025, no source «professions» or aptitude applications are required. Until 30 September 2030, it is possible to start psychotherapy training in accordance with the previous regulation or to complete it by 30 September 2038 (university entrance qualification – propaedeutic course – specialist course).

Malta: a small country can be a good example

The case of Malta shows that a relatively small country can set a fine example. The «EAP back-up» and the European Certificate of Psychotherapy (ECP) standards have proven to be very helpful, but the key engine was the Malta Association of Psychotherapists (MAP), established in 1999, which soon after that achieved the status of authorised National Umbrella Organization (NUO) in EAP. Ever since the establishment they worked closely with the Ministry of Health. The fruit of good cooperation was that in 2003, the Health Care Professions Act included psychotherapy in the list of the professions of complementary medicine.2 In the framework of the Council for the Professions Complementary to Medicine of the Ministry of Health it lasted three years to form the criteria for training and giving out licenses. The process of coordination went on between the representatives of the University studies of psychology, psychiatric clinic, Maltese Assembly of Psychotherapists and the Maltese Gestalt Institute (Oudijk 2002). In September 2006, new criteria became functional that required a Bachelor’s degree (Bologna system) to enter the training, which had to consist of at least 3.200 hours and can last up to four years (as a part time study) or two years (as a full time study) on the postgraduate level of universities or accredited institutes, where the candidates get the postgraduate level acknowledged. All the relevant modalities were acknowledged. Council or the Ministry of Health Care has become responsible for granting the title of psychotherapist and for running the register (Mifsud 2010).

On 20 June 2018, Maltese Parliament voted in favour of the Psychotherapy Profession Act (Act No XXV of 2018) (Malta government 2018) and recognised the autonomy of psychotherapy profession. Two conditions must be met to obtain a license: (1) bachelor’s degree in a human or social science and (2) training in a specific psychotherapeutic modality for a period of not less than 4 years (800 hours theory, 600 hours practice under supervision), or its equivalent of 120 ECTS (Master’s degree). Maltese regulation thus promotes the academisation of psychotherapy education. A good example is the Gestalt Psychotherapy Training Institute Malta (EAPTI-GPTIM), which in 2014 became fully recognised and officially accredited as a Higher Education Institution by the Malta Further & Higher Education Authority (MFHEA) within the Ministry of Education of Malta. Today the Institute can deliver the title of a Master and even a Doctorate in Gestalt therapy (similar to Great Britain) (Pecotić 2024).

Croatia: despite the regulation of psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, access to psychotherapy services for users remains inequitable

Similarly to the Maltese psychotherapists, Croatian psychotherapists, united in the umbrella organisation (SPUH = Savez psihoterapijskih udruga Hrvatske)3, have succeeded in achieving legal recognition of psychotherapy as an autonomous profession, in accordance with EAP standards. On 6 July 2018, the Croatian Parliament adopted the Law on Psychotherapeutic Activity (Croatian Parliament 2022). Unlike in all other European countries, where the Ministry of Health is responsible for the regulation of psychotherapy, in Croatia the Ministry of Social Affairs has taken over responsibility (Prevendar 2019).

Psychotherapy can be provided by a psychotherapist and a counsellor therapist. A psychotherapist must have completed a second degree in psychology, medicine, social work and educational rehabilitation, social pedagogy, pedagogy and speech therapy, and have successfully completed at least four years of education in one of the psychotherapeutic approaches recognised by the EAP and approved by the international umbrella associations for each psychotherapy modality. To be licensed, a person must become a member of the Association and be entered in its register. As membership is not compulsory, many people do not join the Chamber and take advantage of their «free» status.

The counsellor therapist («self-appointed therapist») must have completed a first degree in the same fields as the psychotherapist and have successfully completed at least three years of education in the chosen psychotherapeutic approach, recognised by the EAP and approved by the international umbrella association for that psychotherapeutic approach. However, an individual with a second level of study in other fields may also become a counsellor therapist, provided that he/she has completed a propaedeutic course in psychotherapy and a minimum of three years’ education in the chosen psychotherapeutic approach. A counsellor therapist can provide counselling, supportive therapy and individual and group counselling according to the principles of psychotherapy. Like psychotherapists, counsellor therapists who wish to be licensed to practice therapeutic counselling independently must become members of the Chamber and be entered in its register.

The law did not meet the expectations of colleagues from the SPUH, which, under the auspices of the Ministry of the Social Care, has been prepared for more than ten years (Prevendar 2018). Namely, the version which was adopted in Parliament, was secretly changed by the medical and psychological lobbies a few days before the Parliament session so that retained their privileges. The moral of the Croatian story is that the mere recognition of the autonomous profession of psychotherapist, while improving their status in society, is not enough, because today they are faced with the following problems:

- doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists can continue to charge public health money for psychotherapy services without any systemic check on their competence, leaving it to the responsibility of each individual or the institution in which they are employed;

- psychotherapists are excluded from the public health system and other public networks, such as social care. Their surgeries may be overcrowded, but it is unfair to their clients that they work exclusively for the self-paying. People who cannot pay for their own care are even less well cared for than before the law was passed;

- Chamber of Psychotherapists was established in 2019, but to date it has not established a system of licensing and renewal and has not actively addressed two key problems: inequitable access to psychotherapy services and the almost complete absence of quality checks. A tacit consensus has emerged between psychotherapists and psychiatrists and psychologists, as everyone is doing well financially, while users have once again been short-changed. This is also because membership of the Chamber is not compulsory and many people do not join and also take advantage of their «free» status at the expense of users;

- no public institutions in the health, social care, education and other sectors continue to advertise for psychotherapists;

- access to psychotherapy training is only possible through a previous second profession; training for psychotherapy as a first profession is not possible;

- because counsellors are illogically discriminated against in terms of training conditions, they are rightly seeking the same status as psychotherapists through pending lawsuits before the Croatian Constitutional Court and the European Commission;

- a psychotherapist or counsellor can only start treating a child or adolescent after obtaining medical diagnostic documentation and a proposed indication for treatment. In many cases, this is completely unnecessary and can lead to early stigmatisation, as the information is recorded in the child’s or adolescent’s medical records, which then follow the child throughout his or her life.

Conclusion

Concern for equitable access to psychotherapy and its quality for those in need of such kind of help must be a key criterion and goal in efforts to regulate psychotherapy. Without this, even the legal recognition of psychotherapy as an autonomous profession and scientific discipline makes no real sense and loses its ethical compass. In all the countries illustrated, therefore, regardless of their stage of development, there are many problems in providing accessible and quality psychotherapeutic and other professional services in the field of mental health care. This cannot be achieved once and for all, but requires continuous review and improvement. However, without a good legal framework, the needle on the ethical compass remains without key coordinates. In order to point us in the right direction, which is manifested above all in the unacceptably long waiting times for psychotherapy, it will not be possible without a law defining it according to the advanced international standards of an autonomous profession and scientific discipline. International comparisons clearly show that if psychotherapy remains only in the hands of doctors and psychologists (as a method or specialization), or medicine and psychology, its fate as an eternal orphan is sealed. It will survive but it will not flourish.

Bibliography

Bundesministerium der Justiz (2024). Gesetz über den Beruf der Psychotherapeutin und des Psychotherapeuten (Psychotherapeutengesetz; PsychThG). https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/psychthg_2020/PsychThG.pdf

Croatian Parliament (2022). Zakon o djelatnosti psihoterapije (Law on Psychotherapy). https://www.zakon.hr/z/1045/Zakon-o-djelatnosti-psihoterapije

EAP (European Association for Psychotherapy) (1990). Strasbourg Declaration on Psychotherapy. https://www.europsyche.org/about-eap/documents-activities/strasbourg-declaration-on-psychotherapy

European Commission (2017). ESCO handbook: European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations. European Commission.

European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations (EFPA) & UEMS (European Union of Medical Specialists) (2009). Plans concerning establishing a common platform for psychotherapy and psychotherapists. EFPA and UEMS.

Finlex (2018). Regulation on healthcare professionals. https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1994/19940564

Finlex (2024). Act on healthcare professionals. https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1994/19940559

Gargot, T., Dondé, C., Arnaoutoglou, N. A., Klotins, R., Marinova, P., Silva, R., Sönmez, E. & EFPT Psychotherapy Working Group (2017). How is psychotherapy training perceived by psychiatric trainees? A cross-sectional observational study in Europe. European psychiatry: the Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 45, 136–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.05.030

Grebo, U. & Elmquist, B. (2002). Sweden. In A. Pritz (Ed.), Globalized Psychotherapy (pp. 300–309). Facultas.

Hunt, P. (2020). Submission for a Common Training Framework for the Profession of Psychotherapist. EAP.

Hunt, P., Laurinaitis, E. & Young, C. (2021). EAP Statement on the legal Position of Psychotherapy in Europe. EAP.

Johansson, P. & Fahlke, C. (2019). A study on how basic psychotherapy training is perceived by Swedish physicians in psychiatry. Reflective Practice, 20(4), 417–422.

Jones, J. L. & Mehr, S. L. (2007). Foundations and assumptions of the scientist-practitioner model. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(6), 766–771.

Malta Government (2018). XXV of 2018 – Psychotherapy Profession Act. Malta Government Gazette no. 20.015, 26.8.2018. https://legislation.mt/eli/act/2018/25/eng/pdf

Mifsud, G. (2010). The Position Adopted by the Council for the Professions Complementary to Medicine (Malta) vis-à-vis the Regulation of the Profession of Psychotherapy. Lecture on the European Conference on the Political and Legal Status of Psychotherapists from a Professionals and Clients’ Protection Point of View in the European Union, 18th and 19th of February 2010. EAP.

Možina, M. (2007). V Sloveniji se je začel fakultetni študij psihoterapije (Faculty study of psychotherapy begins in Slovenia). Kairos – Slovenian Journal for Psychotherapy, 1(1–2), 83–103.

Možina, M. (2022). The legal regulation of psychotherapy and counselling as independent professions: what can we learn from Austria? Kairos – Slovenian Journal for Psychotherapy, 16(1–2), 215–283.

Možina, M. (2023). The contribution of Alfred Pritz to the development of psychotherapy in Slovenia. In R. Popp, J. Fiegl & A. Jank-Humann (Eds.), Heilen, Bilden, Forschen, Managen, im Mittelpunkt der Mensch: Festschrift für Alfred Pritz (pp. 235–258). Pabst.

Mistiaen, P., Cornelis, J., Detollenaere, J., Devriese, S., Farfan-Portet, M. I. & Ricour, C. (2019). Organisation of mental health care for adults in Belgium. Health Services Research (HSR). KCE Report 318. Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE).

ORF (2024). Master doch auch an Fachhochschulen möglich. https://science.orf.at/stories/3224538

Oudijk, R. (2002). Netherlands. In A. Pritz (Ed.), Globalized Psychotherapy (pp. 218–224). Facultas.

Pecotić, L. (2024). The History of EAPTI-GPTIM. https://www.eapti-gptim.com/history

Prevendar, T. (2018). Development of Psychotherapy in Croatia. Doctoral thesis. SFU Wien.

Prevendar, T. (2019). The process of establishing and regulating the profession of psychotherapy in Croatia. Kairos – Slovenian Journal for Psychotherapy, 13(3–4), 131–153.

Pritz, A. (2011). The struggle for legal recognition of the education of psychotherapy and an autonomous psychotherapy profession in Europe. International Journal of Psychotherapy, 10, 5–20.

Pritz, A., Fiegl, J., Laubreuter, H. & Rieken, B. (2020). Universitäres Psychotherapiestudium. Das Modell der Sigmund Freud PrivatUniversität. Pabst.

RIS (2024). Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Psychotherapiegesetz. Fassung vom 07.06.2024. https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10010620

Saarni, S. I., Nurminen, S., Mikkonen, K., Service, H., Karolaakso, T., Stenberg, J-H., Ekelund, J. & Saarni, S. E. (2022). The Finnish therapy navigator – digital support system for introducing stepped care in Finland. Psychiatria Fennica, 53, 120–137.

Saarni, S. E., Rosenström, T., Stenberg, J. H., Plattonen, A., Holi, M., Ekelund, J., Granö, N., Komsi, N. & Saarni, S. I. (2023). Finnish Psychotherapy Quality Register: rationale, development, and baseline results. Nordic Journal of psychiatry, 77(5), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2022.2150788

Sasse, C. & Vrancken, P. (2014). Legislation on psychotherapy in Belgium – status February 2014. https://www.europsyche.org/contents/14285/belgium

Sasse, C. & Vrancken, P. (2017). Situation in Belgium – updated as per October 2017. https://www.europsyche.org/contents/14285/belgium

Seikkula, J. (2011). Psychotherapy in Finland. In BundesPsychotherapeutenKammer (Ed.), Psychotherapy in Europe – Disease Management Strategies for Depression. BundesPsychotherapeutenKammer (BPtK). https://www.bptk.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Themen/PT_in_Europa/20110223national-concepts-of-psychoth-care.pdf

Socialstyrelsen (The National Board of Health and Welfare) (2015). Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om läkarnas specialiseringstjänstgöring (p. 8). Socialstyrelsen; SOSFS; 2008:17 och SOSFS.

Statista (2023). Number of psychotherapists in Sweden from 2013 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/966669/number-of-psychotherapists-in-sweden

van Broeck, N. & Lietaer, G. (2008). Psychology and Psychotherapy in Health Care: A Review of Legal Regulations in 17 European Countries. European Psychologist, 13(1), 53–63.

La regolamentazione della psicoterapia nei Paesi europei

Sulla strada della psicoterapia come professione indipendente e disciplina scientifica

Riassunto: Negli ultimi decenni, due processi interconnessi e che si rafforzano a vicenda sono stati cruciali per lo sviluppo della regolamentazione della psicoterapia: gli sforzi per legalizzare la psicoterapia come professione indipendente e gli sforzi per accademicizzare la psicoterapia come disciplina scientifica indipendente. Mentre in Europa l’Associazione Europea per la Psicoterapia (EAP) svolge un ruolo chiave negli sforzi per legalizzare la psicoterapia come professione indipendente, l’accademizzazione della psicoterapia è iniziata nel XX secolo prima a livello post-laurea, dopo la riforma di Bologna a livello di master e dottorato e dal 2005 anche a livello di laurea triennale, prima in Austria e poi in Slovenia e Germania. Brevi descrizioni della regolamentazione della psicoterapia in alcuni Paesi europei – Germania, Svezia, Finlandia, Austria, Malta e Croazia – sono utilizzate per mostrare che l’attenzione alla parità di accesso alla psicoterapia e alla sua qualità per coloro che hanno bisogno di questo tipo di aiuto deve essere un criterio e un obiettivo centrale negli sforzi per regolamentare la psicoterapia. Il confronto internazionale mostra anche che la psicoterapia sopravviverà, ma non fiorirà, se rimarrà esclusivamente come metodo o specializzazione nelle mani di medici e psicologi.

Parole chiave: regolamentazione della psicoterapia, Dichiarazione di Strasburgo, accademizzazione, psichiatria, psicologia, salute mentale

Biographical note

Mag. Miran Možina, MD, is psychiatrist and psychotherapist, director of the Sigmund Freud University Vienna – Ljubljana branch (SFU Ljubljana). Since 2006 he is teacher and researcher in the field of psychotherapy science and history of psychotherapy.

Contact

2 There are as many as 18 professions on this list, in addition to psychotherapy also acupuncture, chiropractic, dietetics, dental hygiene, occupational therapy, nutrition, osteopathy, physiotherapy, radiography etc.