How the Oaklander Model sparked a Global Community of Therapists in a Pandemic, and enriched Training and Treatment

Karen Fried

Psychotherapie-Wissenschaft 13 (1) 2023 59–69

www.psychotherapie-wissenschaft.info

https://doi.org/10.30820/1664-9583-2023-1-59

Abstract: Social isolation caused by COVID threatened psychotherapist-client and instructor-learner contact especially in the child therapy field. In response, the author devised free online Oaklander Model interactive play therapy tools (Sandtray, Puppets, Dollhouse, Projective Cards, Mindfuldraw) which replace their hands-on originals with tabs of images clients choose, place, move, enlarge or shrink, and make act and speak to orchestrate scenes. The author also conducted teleconference training and supervision in their use. Both the digital interventions and instruction continue to attract therapists from some 30 countries, who collaborate to support children from afar. The technological recasting of play techniques and teaching proved to retain and even expand their powers along with their reach. Such expansion confirmed the universal, timeless efficacy of Oaklander’s interventions and approach, and their applicability to virtual platforms. It also increased client access to therapy and therapist access to clinical education, regardless of location and finances. Finally, it revealed advantages of remote play therapy and training: recording sessions or stages of client creations, including from separate devices; shot sharing of clients’ home, household members, pets and meaningful objects for assessment and exploration; environmental sustainability of foregoing transportation, office rental, physical art materials and storage; and construction of an international therapeutic community sharing their knowledge. Periodic polling, current website analytics and a recent formal survey show these techniques and gains have outlasted and outgrown lockdown despite distance, financial hardship and, sometimes, war. Digital therapy, learning and collaboration endure and expand both online and live as the foundation of this network’s dual achievement: a global community of healers and a global extension of healing.

Keywords: Post-Pandemic teletherapy, online Violet Oaklander Model, online play therapy, interactive play teletherapy

The isolation COVID-19 initially imposed between child psychotherapists and clients and between supervisors and trainees threatened all aspects of care. In response, development of digitized Oaklander Model interventions, supervision and teaching introduced tools and therapeutic community which have outlived the lockdown. They confirmed the efficacy and applicability of Gestalt play therapy to virtual modes of treatment and to practitioner education and collaboration. As well, they demonstrated specific benefits distance work offers clients and therapists, including access irrespective of location and resources. With modifications to in-person sessions and training, a digitized Oaklander Model appeared to retain and even extend its treatment power and availability and to advance the field by connecting practitioners. The experience suggests that both use of and instruction in remote interactive play therapy are and should be here to stay in both virtual and live venues. Recurrent polling, websites analytics, and an extensive survey of participants corroborate this finding.1 And it is illustrated by the cultivation of an enduring global network of Oaklander Model therapists and by outcomes for clients they helped in new ways and places.

Rationale for Online Oaklander Therapy

The pandemic tested the utility of Oaklander’s model in a wholly novel format. Remote sessions with adults already had a footing (Smith et al., 2021) and teletherapy for marginalized families had garnered interest (Beel, 2021). But the pandemic required the transformation of Oaklander’s tactile, client-led, interactive play therapy into a structure that was user-friendly for therapists unaccustomed to virtual work, of whom Sampaio et al. (2021) wrote. Concerns included whether a distance setup might weaken the interventions and whether distance teaching might flatten their fine points.

To the contrary, digitized Oaklander tools seemed to engage isolated youngsters ably (Bolton et al., 2021) and on-screen supervision and teaching let trainees and colleagues fully master their use. The model’s principles; evaluative and therapeutic functions; and applicability to varied approaches, diagnoses and contexts explain its functionality on remote platforms.

Principles

Oaklander’s model aims to empower childrens’ sense of self and connection with supportive others by weaving Gestalt concepts and developmental theory into experiential, interpersonal interventions (Mortola, 2001). These creative – thus necessarily projective – activities let them contact their senses, emotions and thoughts, «gain a […] sense of […] their capabilities» and establish genuine relationships (Mortola, 2006, pp. 12–13).

Her application of Gestalt principles to the moving target of an evolving self employs playful projective exercises to illuminate emotional and behavioral issues in ways a child can grasp: Youngsters may be less verbal, and it is «easier» and «safer» to talk about difficulties through, say, puppets (Oaklander, 1978, p. 104). That safety lets them discover, express and integrate ignored polarities, or aspects of themselves. In turn, integrated internal contact brings a sense of themselves as an «I» permitting an I-Thou relationship: «If the self is weak and undefined, the boundary is fuzzy and contact suffers» (Oaklander, 2001, p. 46). Increased through therapeutic partnership, inner and outer contact lets the child regulate, and protect, the self.

Evaluative and Therapeutic Uses

Oaklander’s techniques reveal and advance children’s maturation levels. The first step, evaluation, hinges on client choices from well-stocked instruments which, as Mortola (2006, p. 29) quoted, «tell[ ] us that those images […] touch[ ] something important in them». Client creations thus speak with «a symbolism that substitutes for words» (Oaklander, 1978, p. 106). Klem (1992) presented clinical evidence of dollhouse work’s utility in disclosure and resolution through client-led ritualized play, while Bernier (2005) found puppets valuable in psychological and intellectual evaluation and essential in revealing and processing trauma. Despite the method’s hallmark individuation, a wealth of pre- and post-treatment studies and reports of researchers and clinicians attests to its evaluative and therapeutic efficacy (Bratton et al., 2005; Carroll, 2015; Wheeler & McConville, 2002; Mortola, 2006).

Applicability

In fact, the model’s evaluative and therapeutic utility seems to stem precisely from its individuation – a holistic view of the child in a specific environment, analysis of the child’s developmental stage, and tailored, client-driven treatment. The publication of Windows to Our Children in 17 languages; Hidden Treasure’s release in 7 languages; and the current narrative signal its flexibility.

The model’s application to a range of therapies, pathologies and contexts suggests the same. Courtney (2008) and Gil (1991) identified the dollhouse as indispensable in any child therapy. In their meta-analysis of 93 studies gauging the effect of play therapy, Bratton et al. (2005) cited Oaklander’s approach as central to the field. Oaklander’s techniques, which playfully but persistently elicit youngsters’ decision-making, nonverbal and verbal expression, and relationship with a trusted therapist, appear both effective and fitting in a time of collective trauma and private loneliness (Bolton et al., 2021; Strauch, 2021).

Digitizing Oaklander Interventions and Training

During lockdown, the author developed free online Oaklander Model tools2 and training (Fried, 2020a, b) so the author and supervisees could continue client care. To fulfill the model’s aim of exercising client choice in creating scenes, the instruments had to offer opportunities equivalent to those enabled by physical objects.

Research suggests virtual tools do permit high levels of immediacy, intensity, confidentiality, and outcome in both conscious and unconscious realms (concerning onlinesandtray.com, see Bolton et al., 2021; Strauch, 2021). They also offer multi-client access, unlimited storage of screenshots or sessions, and client choice of medium. And virtual instruments, notably the author’s Sandtray, have been seen to facilitate graduate education in play therapy (Swan et al., 2022; other sand tray sites exist and charge for use).

Instructions

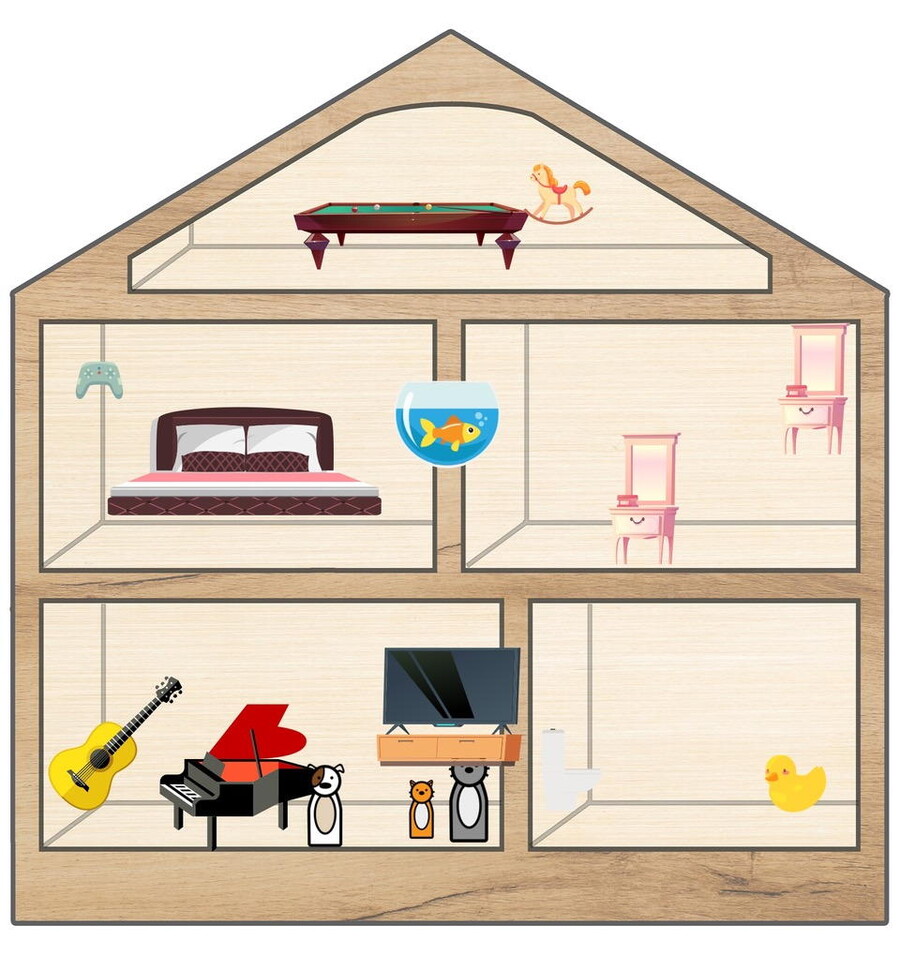

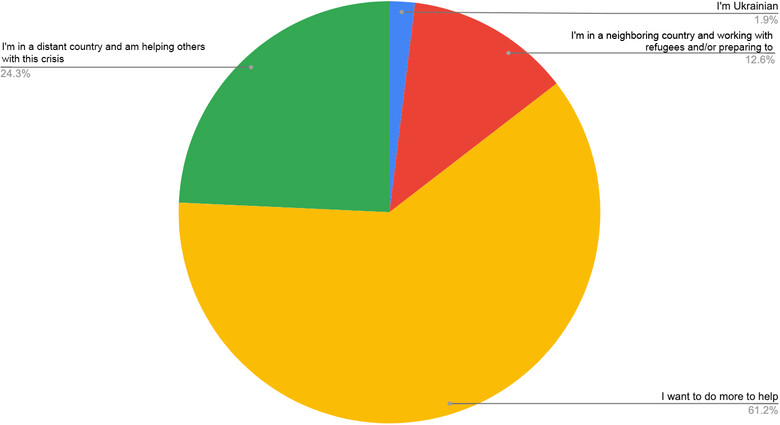

To retain the originals’ benefits, except for Mindfuldraw these remote tools require client/s and therapist to use computers and visit the site. Clients may share their screen, accept remote control, or direct the therapist how to build a scene. First, the therapist invites client/s to browse placeable images of human, animal and fantasy figures and items – 213 figures and some 320 items in Sandtray (Fig. 2), about 220 items in Dollhouse (Fig. 3) and 32 figures in Puppets). Option buttons let clients enact scenes:

- Click on an image to add it to the scene.

- Click on an image, then on Delete to remove it.

- Click on an image and drag it to enlarge or shrink it.

- Click Copy to add any number of image duplicates.

- Click Flip to make a figure face the other direction.

- To place a figure in front of or in back of another, select the figure, click on Back or Front and drag to the other figure.

- Click to Save the scene.

- Click to Clear the scene.

As do the originals, remote Sandtray and Dollhouse each have one stage while Puppets offers 8 backdrops and additional action options:

- Click on one, some, or All puppets, then click on Hug, Speak, Hit, or Jump to make them do so.

As in a live venue, the therapist explores the client creation as a projection:

- Prompt client/s to imagine a scene.

- Ask client/s to make their scene.

- Ask client/s to describe their scene.

- Use projective exercises:

- Ask them to be one or some of the figures and explore the figures’ feelings and thoughts.

- Encourage reflection on the projection:

- «Does the scene make sense for you?»

- Ask if client/s would like to add or change anything in it.

- Let client/s add, delete, move, resize images.

- Save the scene.

Mindfuldraw

Similar to its in-person mode, the virtual sketchpad lets clients experience designing multimodally – set Brush Stroke Width.

- Click Brush Color, then click desired color.

- Click Brush Fade and drag to set image retention for up to 60 seconds.

- Click Sounds to select desired sound.

- Click Loop for continuous sound, or Timed, and desired interval.

- Click Brush Style, then either Line or Blot.

Projective Cards (Fig. 1; Fig. 4)

As in person, the therapist explores the card chosen out of 55 as a projection through prompts:

- How are you feeling right now? Pick a card that goes with that feeling.»

- Invite client/s to browse cards and click to enlarge one.

- Now, pick a card for how you would like to feel.»

- Can you pick a card that goes with one of the core emotions – sad, mad, glad, and scared?»

- Pick a card that represents your past … present … future.»

The applicability of Oaklander tools and training in them to a virtual format also held internationally, when a spring 2020 presentation the writer had set in Italy and COVID reset on Zoom spread demand for these among therapists abroad. Their interest led to one more, then another, then an ongoing series of videoconference calls and classes. This forum let therapists connect and consult across space, time and even physical ability: Violet Oaklander, in her 90s, participated despite the impact of age on her hearing, mobility and sight.

In brief, the flexibility of the remote tools and training upended the expectation that their use would be short-lived, disproving the «Just for Now» assumption which had titled the author’s first article and calls on the subject (Fried, 2020b, c). Embracing virtual therapy and courses in their own right and not as sorry substitutes for live sessions and classes has permanently enriched both: It expanded Oaklander therapists’ understanding of «Now» to mean not temporary but «the present» and added the quality of «Here» meaning not nearby but «wherever the client or learner is» – an amplification of the «Here and Now» applauded by child Gestalt therapist Oaklander.

This reply to pandemic separation underscored the resilience of the client-therapist and instructor-learner connection across space, time zones, and technology. It showed a commitment to seeing and hearing others – a testimony healing and educational in itself.

A Therapeutic Response

Harnessing technology at the height of COVID, therapists the world over built a collaborative community, deepened their expertise, enhanced individual practice, and definitively recast treatment and training as freely available yet responsive to local need.

Global Community

Intended to present the «Just For Now» article in mid-March 2020, the call accomplished much more; Oaklander and participants from afar so enjoyed conversing that all were invited to reconvene the following week. On that call, mention of the author’s establishing the Violet Solomon Oaklander Foundation (VSOF) to continue her work elicited an immediate request from Mirela Badurina of Bosnia and Herzegovina: The BHIDAPA Center in Sarajevo, which teaches and researches integrative psychotherapy for migrant families, wished to translate for their website the manual, Just For Now: Virtual Use of the Oaklander Model in a Time of Crisis (Fried, 2020b) – a resource delivered free which they still use. The second Just For Now (JFN) call let her thank Oaklander personally for Windows – the only book on youngsters available after the war in then-Yugoslavia.

On the calls therapists Michal Cernik in the Czech Republic and Jennifer Brury in San Francisco shared what they felt got lost in remote meetings and masking. In May 2020 this author introduced Soledad Pauletti of Argentina to two therapists in Italy, Chiara DeGale Esposti and Ornella Cavalluzzi – experts in supporting teachers’ social-emotional learning to increase their availability to students – so Pauletti could do the same for teachers in Argentina. And in a May 2020 poll, 84.2 % of respondents shared with colleagues information culled from JFN calls.3

That June, racial unrest after the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor drew Christina Morse to present to JFN participants «Racism in America» detailing her experiences as a person of color in Los Angeles. On a call soon after, Shlomy Kattan of Uruguay, now also in Los Angeles, met other therapists from his country. And the next month, Laura Saldarriaga of Colombia presented her therapeutic use of The Little Prince, as participants held up varied translations of the work. Her later comment wishing «Just For Now» meetings would be «just for always» proved prophetic, as one pandemic-era call resulted in 29 to date, first weekly, then monthly, now quarterly. Each drew 80 to 100 therapists from some 30 countries, teaching and learning how to heal youngsters and families despite isolation, poverty and, sometimes, war. The «Just for Now» articles and VSOF manual were translated into 6 languages and guided therapists in their virtual care of children and families (Fried, 2020a, b; Fried & McKenna, 2020). Shared insights of that global community permanently reshaped individual practitioners’ work, and calls still gather some 50 participants from over 20 nations.

Individual Teaching and Practice

Stemming from the JFN calls and training in remote Oaklander interventions, in the US Jackie Flynn of Florida now teaches EMDR using onlinesandtray.com; David Crenshaw in New York trains interns with that instrument; and Dana Wyss of Los Angeles employs it her online sessions. Using all the online tools the author developed, even when training live, lets learners offer them to their clients. Widening its impact, in the fall of 2020 Tammi Van Hollander in Philadelphia used onlinesandtray.com to teach Chinese play therapists via a series of Zoom events. And Laura Saldarriaga of Colombia translated and sent records (lightly edited, below) of an ongoing case referred to her by a JFN colleague in August 2021. The case exemplifies both distance and live use of these online Oaklander tools, and demonstrates their advantages.

The Case of «Gil»

«Gil», a male-identified 11-year-old 5th grader, presents as intelligent and sweet, and is of small stature and well-dressed. His speech sounds adult, with sophisticated terms describing computer programming, video games and robotics. His longstanding fears of germs (e. g., in movie theaters) and heights, and his habitual retreat from them through isolation, were exacerbated by the pandemic. While he minimized his concerns – «everything is fine» – he was the only child to wear a mask and would not attend school without one. Gil ate and slept as usual but since the pandemic wanted only to sit in his room.

The client came to therapy because his parents saw him as increasingly worried, unhappy and non-social, although he interacted politely with peers. The close-knit, supportive and very sociable family appears to treat Gil kindly and to set limits gently. Gil’s father directs a tech company and Gil often accompanies him to the office and speaks intelligently with employees. In fact, conversing with adults seems to be the client’s comfort zone. Gil had had no previous therapy and it was hoped therapy would give him space to talk about his feelings. In August 2021 a JFN participant referred the case to the therapist, who employed Oaklander’s approach with both live and virtual tools, shifting to remote-only instruments after Gil’s family moved to Uruguay.

Despite Gil’s anxieties, he was comfortable enough with the therapist to forget to wear a mask in session. Still, his underlying and current COVID fears clarified why he avoided socializing. Again, Gil himself did not see that connection, stating that he just likes solitary pastimes. So at the start of therapy the therapist asked Gil to pick a projective card that shows how he was feeling right then. He picked the Mouse (Fig. 1), which drew him to talk about the mouse’s difficulty understanding friends and making new ones: «[W]hen they are talking about a topic, I get lost […]. A little alone, the socialization part […]. There are times when inside me I don’t understand the feelings of my friends […]. I wish to understand how to make new mouse friends.»

Fig. 1: Mouse Projective Card

Another early intervention confronted more realistic social fears, using projective puppet play to help him handle bullying boys at school. He remains proud of this victory because the boys now respect him, and often brought his puppet Banané to sessions.

Raising Gil’s anxiety was his family’s plan to leave Colombia and return to their native Uruguay. Gil resisted discussing this as well as his other fears and the therapist honored his resistance. Fortunately, online tools used both remotely and in person kept a sense of stability despite the upcoming relocation. Gil visited onlinesandtray.com to represent what he liked about Colombia: «traditions, kind people, how they talk, the weather, and biodiversity.» Sharing that he wanted more about Colombia in the scene, he managed to create freehand and centrally display the Colombian flag (Fig. 2). Thus the virtual tool engaged Gil’s interest in electronics to help him discover, express and relieve some grief and anxiety about leaving Columbia.

Fig. 2: Sandtray Celebrating Colombia

With the online dollhouse (Fig. 3) Gil designed his wished-for new home and life in Uruguay. He was so happy with his creation, which further reduced his relocation concerns, that he shared it with his mother, who in turn shared it with the architect planning their new residence.

Fig. 3: Dollhouse Design for Uruguay Home

In October 2022, Gil picked the Tree projective card (Fig. 4) as depicting how he was feeling: «I am a tree, I am full of possibilities, I can do more things now, I can make friends, and do anything I want, feel much better.» His card choice and interpretation show significant resolution of his anxieties even when therapeutic work had become fully remote.

Fig. 4: Tree Projective Card

On a JFN call Saldarriaga explained why she employed online instruments with Gil, as with others, even when in person: Equipped with her iPad she can practice at any locale and keep secure records of clients’ evolving creations. Most important, offering online instruments in live sessions gives youngsters a developmentally crucial opportunity to choose.

International Training, Partnerships and Conferences

The therapeutic collectivity shared this and other examples of practitioners’ pandemic- and post-pandemic teaching and treatment with distance Oaklander tools (Fried, 2021), and produced virtual courses, partnerships and conferences broadening its educational scope. In the US, Susan Dorn of Seattle, Oregon, started an online monthly Oaklander Model peer group, which therapists from abroad continue to join. After the March 2020 JFN meeting Giandomenico Bagatin created Gestalt Play Therapy Italia and still hosts monthly «community meetings» in Italy, often with this author’s and other VSOF members’ presentations. From one of the nations hit hard and early by COVID, he was among the first to describe its devastating effects on a call.

This writer’s in-person April 2020 training in Italy, hastily rescheduled as a Zoom for Italian speakers, permitted Tzvetta Misheva-Aleksova from Bulgaria and Seema Omar from Sri Lanka to meet. They now collaborate, as Omar asked Misheva-Aleksova to teach storytelling to counselors in Sri Lanka. Misheva-Aleksova herself founded Gestalt Play Therapy Bulgaria, and sponsored a 70-hour training with practitioners, some of whom she had met on JFN calls.

In December 2020 Saravejo’s BHIDAPA Center hosted a UNICEF-sponsored conference, «Here and Now: Achieving Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing, Second International Congress of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy (Bosnia and Herzegovina)». Along with Mirela Badurina, the author collaborated with Tea Martinović, Sabina Zijadić-Husić and Senka Cimpo. Badurina had also invited JFN colleagues Jon Blend from the UK, Giandomenico Bagatin from Italy to present. Blend conveyed music, poetry and his own singing over Zoom. Conference attendees shared his interview with the author about the JFN calls.

On a call the next month, Zorica Topalovic from Croatia said, «My dream is to have this model taught with people from my country, in my language». This writer responded, «I just spoke with Vesna Hercigonja Novkovic from Croatia», to which she replied, «That’s my institute!» Shortly after, the author trained her group. On the February 2021 JFN call Bernadine Anderson from Kenya, Hamida Ahmed and Sylvia Guerra from Italy, and Erica Rothblum from the US reported on the pandemic’s impact on schoolchildren.

May 2021 marked the first VSOF conference, with presentations filling 3 days and running 24 hours a day to accommodate varied time zones. Half of the 38 presenters came from outside the US; most had been invited through JFN calls; all were treated to a dramatic JFN call at the conference’s culmination: Near the start of the pandemic Wendy Esterhuysen of the UK volunteered that she had been at a conference 21 years earlier in South Africa at which Oaklander conducted workshops. She connected this writer with its organizers, which let the community reunite Oaklander with the workshop participants. Prominent among them were her hosts, Hannie Schoeman and Retha Bloem–whose story about Oaklander’s interaction with her then-3-year-old was saved to YouTube. Oaklander scholar Peter Mortola, also at that conference, presented photos and insights about their collaboration. And Florence Mueni of Kenya waved her well-worn Windows (as did Daria Bocharova from Moscow and Giandomenico Bagatin from Italy) in thanks. And after Oaklander’s death 4 months later, over 100 colleagues worldwide convened virtually to honor her.

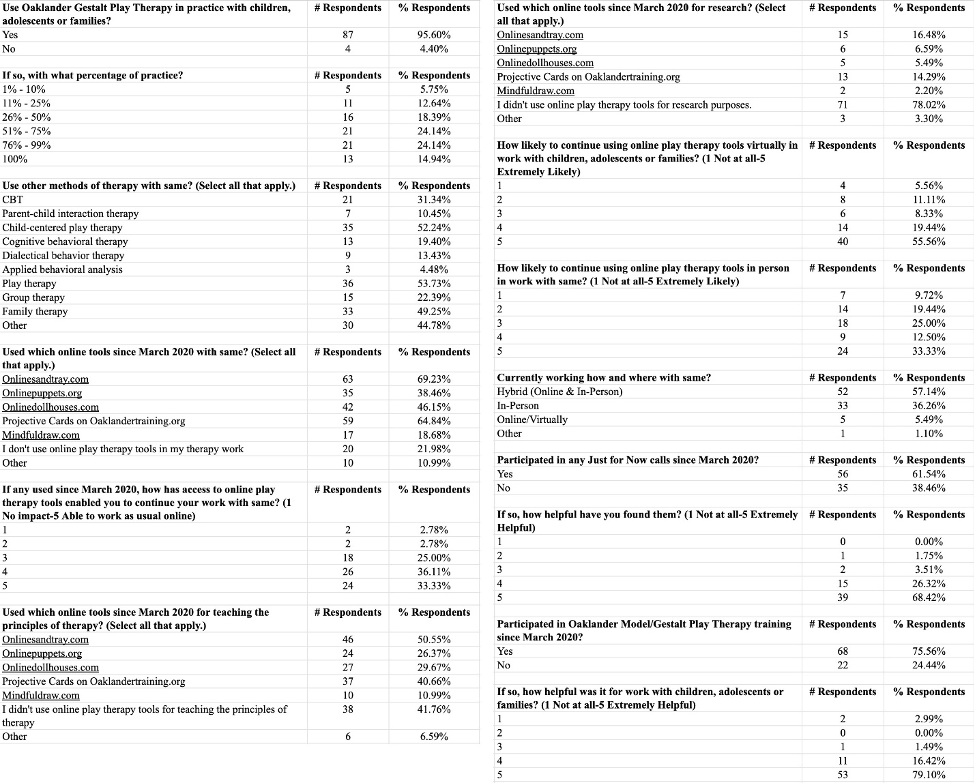

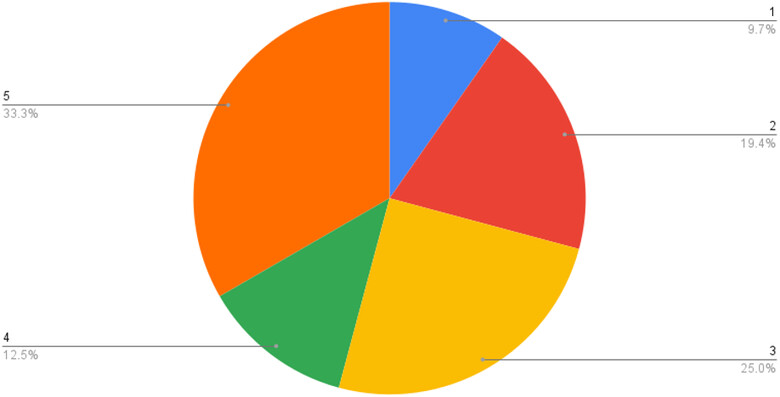

This therapeutic sphere often responded to the psychic damage of political conflict. In September 2022, Mzika Dalakishvili and Magda Machavariani from Tblisi, Georgia (former Soviet Union), principals of Gestalt Play Therapy Georgia, offered a 70-hour training spanning several weekends, at which the author and other VSOF participants presented. Early the next month, Catherine Pestano, a social worker in the UK, recounted the effects of the war in Ukraine on refugees and how she served them. Nataliya Bulatevich of Ukraine, who had joined the JFN calls at the start of hostilities, had just enough time to receive participants’ best wishes before the evening blackout in Kyiv. In fall 2022 the author began free supervision of 30 Ukrainian therapists – half of them limited to phones – whose poignant questions concerned managing clients’ grief and trauma while they themselves share those emotions. And serial polls through fall 2022 measured JFN participants’ efforts: 12.62 % of respondents in nearby countries were working with refugees or preparing to; 24.27 % were helping from afar; and 61.17 % aimed to (Fig. 5).4

Fig. 5: Efforts for Ukraine

Upcoming conferences will maintain the same free access and local responsiveness. Spanish-speaking practitioners in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and Spain will meet monthly from January to September 2023 for a 70-hour training in the Oaklander Model. This writer will deliver a keynote address and lead one workshop at the 15th Play Therapy Conference in Mexico in May 2023. And the VSOF conference set for 2–4 June 2023 is planned as a remote/live hybrid event: Staggered Zoom presentations will match time zones, and satellite locations will offer in-person gatherings. For example, Laura Urquiza and Soledad Pauletti of Argentina, who met through JFN calls, will co-host a live venues. Each satellite will detail its events on a last-day JFN call.

Polls, Analytics and Survey: Durable Digital Therapy

Three instruments investigated the durability of virtual Oaklander tools, training and the collective deploying them.5 Periodic polls of JFN participants tracked their rise from May 2020 to October 2022. By the first half of 2022, 86.27 % of respondents aimed to use telehealth after COVID – more than the 82.23 % of respondents working all or partly remotely in April 2021 – implying they anticipated its value beyond pandemic necessity. Indeed, in October 2022, 51.35 % employed online tools although polls since February 2022 showed 65 % had few COVID restrictions. And January 2023 monthly websites analytics tallied 32,310 visitors from 114 countries – 24,590 to Sandtray, 4,840 to Dollhouse and 2,880 to Puppets.

January 2023 survey data (condensed in Fig. 6)6 speak to the future of Oaklander tools, learning and collaboration based on their applicability in therapy, teaching and research; feasibility in both distance and live work; and contribution to clinical expertise.

Fig. 6: Condensed Survey

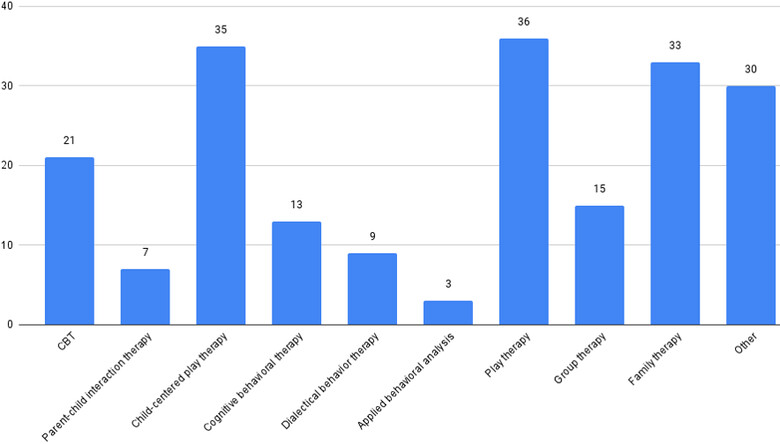

Of 91 respondents from 30 countries, 95.6 % apply the Oaklander Model with children, adolescents or families – nearly 50 % with about half to almost all clients. Yet Fig. 7 shows how many also use varieties of Play, Cognitive Behavioral, Family, Dialectical Behavior, Group, and Parent-Child Interaction, evidencing the model’s flexibility.

Fig. 7: Adjunctive Therapies

Since March 2020, nearly 70 % of respondents practiced with Sandtray and Projective Cards, followed by Dollhouse, Puppets and Mindfuldraw tools; fewer than a quarter used none. Nearly 70 % stated these let them work exactly or nearly as before COVID. Of respondents using them, 75 % rated it Extremely or Highly Likely they would continue to do so virtually, and almost 46 % rated it Extremely or Highly Likely they would use them in person – a litmus test for their post-COVID functionality (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: Planned Post-COVID Online Tool Use (1: not at all likely – 5: extremely likely)

The over 50 % of respondents teaching with the tools most commonly employed Sandtray and Projective Cards; the under 20 % using them in research favored the same, though some 81 % used none.

Also since March 2020, 61.54 % of respondents participated in JFN calls, of whom 94.73 % found them Very or Extremely Helpful. In that same period nearly 76 % participated in Oaklander/Gestalt play therapy training, of whom 95.52 % rated it Very or Extremely Helpful. In brief, the polls, websites analytics, and survey suggest distance Oaklander Model tools, education and collaboration have ensconced themselves in the field of child, adolescent and family healing.

Maximizing Outcomes of Virtual Interventions

The community learned that some adjustment to a live format, and readiness to utilize virtual therapy’s specific powers, facilitated successful treatment in lockdown and after:

Confirm Technological Requirements: Except for mindfuldraw.com, which needs only a videoconferencing device, all sites the author developed require client and therapist access to a desktop computer to use, share and save. Clients need a mobile device to send the therapist a «home tour» or real-time shots of persons, items and pets. While such information and affect can be elicited and conveyed just by the therapist’s questioning (see sample, below), the client’s being at home helps achieve this benefit of teletherapy.

Preview Sites: Each site offers directions for its many image and action choices, which therapists should examine before offering the activity.

Record: Therapists can securely record and store entire sessions or screenshots from any number of clients and devices for sharing or review.

Prepare Client/s: With the help of parent/s or caregiver, practitioners should set readying rituals to replace the drive-and-waiting-room transitions to in-person sessions: snack, restroom break, setting a chair or cushion, turning on the computer (Smith et al., 2021). Household members should respect the client’s need for privacy even if they participate in all or part of a session.

Pace: Virtual therapy in an age of «Zoom Fatigue» can make assessing and maintaining client focus hard. Therapists should prepare choices of activities in case client attention, or tolerance for challenging work, flags.

Use the Client Home: As noted, remote therapy can involve the client’s home as a character itself. Any videoconference-ready device lets clients send a «home tour» or introduce pets, household members, and objects to the therapist. Yet even without such devices therapists can observe and inquire about qualities of the home, encouraging clients to use their senses, actions, sounds and words to perceive and describe its qualities:

- What are the most common sounds in your home? What are your favorite sounds? Your least favorite?»

- Clients can describe, write about, or make those sounds, which may include a barking dog, sibling/s yelling, traffic, music, or preparing food.

- Follow up on responses: «Are the sounds loud? Quiet? Musical? Muffled? Calming? Upsetting?»

- What are the most common sights in your home? What are your favorite sights? Least favorite?»

- What are your favorite spaces? Least favorite?»

- Clients can take the therapist on a tour of favorite/least favorite spaces or draw them for the therapist.

- Increase expressive spoken or written language: «Is that space warm? Cool? Quiet? Private? Shared? Small? Large? Comfortable? Exciting?»

Therapists may also inquire about any home item and experience characterizable by touch, smell, and taste.

Contraindications

Assuming client access to basic technology, the main contraindication for online interactive play therapy, as Smith et al. (2021) cautioned, occurs when children are in an unsafe household. The author extends this to those in conflictual albeit not abusive settings, to clients of any age, and to any home-based teletherapy.

Extreme client or family resistance to virtual play as «juvenile» or «Zoom Fatigue» threaten its efficacy, but enthusiastic therapist presentation of interventions usually overcomes these.

Conclusion

Enduring Benefits of Remote Training and Treatment

As indicated by repeated polling, updated website analytics, and a recent survey, therapists’ use of technology to connect with clients and colleagues during lockdown overcame and outlasted its threats of isolation and social inequity. Professionals, trainees, youngsters and families gained, and continue to gain, from the inclusive techniques and partnership healers cultivated. This is so because the advantages specific to virtual training and treatment also outlived the pandemic and pertain currently. Cost-free, near-universally accessible education and collaboration for practitioners, interns and researchers have increased and promise to increase further knowledge about treating children and families. Therapists can deliver, so clients can partake of, treatment despite distance, poverty and, to some extent, political turmoil. Such availability has been recognized as favoring client attendance and thus improving outcome (Smith et al., 2021).

Added to the geographic and financial accessibility of a remote platform are other capacities of lasting value. Primary is its ability to share and store any number of sessions and text or visual creations (including of multiple clients from separate devices), which aids in therapist and client review of an evolving scene, series of scenes, or scenes by different participants (Bolton et al., 2021). Along with this moment-by-moment and multiple-contributor record, remote work permits the therapist to encounter the client’s home as an element – almost a character – in assessment and treatment (Smith et al., 2021; see sample intervention, below), as well as the client’s household members, pets and belongings. Another merit is that international collaboration heightened therapists’ cultural sensitivity. For example, JFN participants learned that some dollhouse builders are familiar with grass roofs rather than European shingled ones, and live in family configurations with which Westerners are unfamiliar – insights crucial for developing treatments translatable to all in this continuously opening circle. Finally, teletherapy sustains more than families’ and practitioners’ budgets: By replacing physical objects with arrays of images clients choose and manipulate to enact scenes, teleplay demands no traffic, office rental, purchase of supplies, nor storage of works and records, and thus sustains the environment.

Digitized Expansion of the Oaklander Model

Social isolation inflicted by the pandemic threatened to dissolve relationships between psychotherapists and clients and between instructors and students – especially those predicated on Oaklander’s individuated, creative, client-driven and relational approach. The response of crafting online supervision, education and tools true to that model drew together learners, practitioners and clients separated by lockdown, geography, poverty, or war. In so doing it deepened clinicians’ knowledge; invited observation of clients’ homes, household members, pets and treasured objects; and recorded their words and creations. Thus remote training and treatment formats have proven not just to maintain but to expand their originals’ powers. That expansion confirmed the efficacy of Violet Oaklander’s model even on virtual modes, and increased client access to the benefits of remote play therapy and therapist access to learning and consultation – all regardless of geographical and financial obstacles to classic sessions and study. This silver lining of the COVID cloud brought successful outcomes to children and families in more places and social classes than ever, and grew a worldwide collaborative sphere of Oaklander Model therapists. That team learned to support participants and clients from afar in uniquely accessible, recordable, culturally sensitive, individuated and sustainable ways that therapists continue, and should continue, to employ both remotely and live after COVID wanes. Virtual training in Oaklander’s online play techniques endures as foundational to this network’s two-fold achievement: a global community of healers and a global extension of healing. This accomplishment has proven as valuable, and as viable, in a pandemic as in a post-pandemic world.

References

Beel, N. (2021). COVID-19’s nudge to modernise: An opportunity to reconsider telehealth and counselling placements. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 1–17. https://www.academia.edu/50972086/COVID_19_s_nudge_to_modernise_An_op portunity_to_reconsider_telehealth_and_counselling_placements

Bernier, M. (2005). Introduction to Puppetry in Therapy. In M. Bernier & J. O’Hare (Eds.), Puppetry in education and therapy: Unlocking doors to the mind and heart (pp. 127–134). Authorhouse.

Bolton, C., Thompson, H., Spring, J. A. & Frick, M. H. (2021). Innovative Play-Based Strategies for Teletherapy, Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2021.2011814

Bratton, S., Ray, D., Rhine, T. & Jones, L. (2005). The efficacy of play therapy with children: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcomes. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 376–390.

Carroll, F. (Ed.). (2015). International Gestalt Journal, 32(2).

Courtney, J. (2008). The perfect dollhouse. Play Therapy Magazine, 3(2). http://www.janetcourtneyphd.com/about_play_therapy.htm

Fried, K. (2020a). Just for Now: Virtual Use of the Oaklander Model in a Time of Crisis: The Full Nest: Working with Adolescents. https://www.vsof.org/fm_articles.html

Fried, K. (2020b). Just For Now: Virtual Use of the Oaklander Model in a Time of Crisis. https://www.vsof.org/fm_articles.html

Fried, K. (2020c) Just for Now Videoconferences [YouTube video series]. Oaklander YouTube Channel. https://www.oaklandertraining.org

Fried, K. (2021). When «Just for Now» Meets the Future: A Case Study Using the Oaklander Model to Transition from the Pandemic. https://www.oaklandertraining.org

Fried, K. & McKenna, C. (2020). Healing Through Play Using the Oaklander Model: A Guidebook for Therapists and Counselors Working with Children, Adolescents and Families. N. N.

Gil, E. (1991). The healing power of play. Guilford Press.

Klem, P. (1992). The use of the dollhouse as an effective disclosure technique. International Journal of Play Therapy, 1(1), 69–73. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc2636/m2/1/high_res_d/Dissertation.pdf

Mortola, P. (2001). Sharing disequilibrium: A link between Gestalt therapy theory and child development theory. Gestalt Review, 5(1), 45–56.

Mortola, P. (2006). Windowframes: Learning the art of Gestalt play therapy the Oaklander way. Gestalt Press.

Oaklander, V. (1978). Windows to our children: A Gestalt Therapy approach to children and adolescents. Real People Press.

Oaklander, V. (2001). Gestalt play therapy. International Journal of Play Therapy, 10(2), 45–55.

Sampaio, M., Navarro-Haro, M.V, De Sousa, B., Vieira Melo, W. & Hoffman, H. G. (2020). Therapists Make the Switch to Telepsychology to Safely Continue Treating Their Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Virtual Reality Telepsychology May Be Next. Front. Virtual Real, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2020.576421

Smith, T., Norton, A. M. & Marroquin, L. (2021). Virtual family play therapy: A clinician’s guide to using directed family play therapy in telemental health. Contemporary Family Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09612-7

Strauch, V. R. F. (2021). Online psychodrama with children and the psychodramatic sandplay method. Revista Brasileira de Psicodrama, 29(2), 99–106.

Swan, A., Yee, T., Wolfram, C., Cameron, A. & Elder, H. (2022). Transforming Graduate Play Therapy Instruction to Virtual Learning During COVID-19. International Journal of Play Therapy, 31(4), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000183

Wheeler, G. & McConville, M. (Eds.). (2002). The heart of development: Gestalt approaches to working with children: Adolescents and their worlds (Vol. 1: Childhood). Gestalt Press.

The author

Karen Fried, Psy.D., M. F. T. is a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and an Educational Therapist in Santa Monica, California. She received a PsyD and Master’s degrees in Clinical Psychology and in Psychology of Human Development, along with certification in Educational Therapy. She has a private psychotherapy practice and co-directs the K&M Center, which provides educational and remedial services to students from preschool to college. In her practice, she uses the Oaklander Model of child therapy, and is president of the Violet Solomon Oaklander Foundation. She trains and supervises child and adolescent therapists in this model in the US and internationally.

Contact

2 http://onlinesandtray.com; http://onlinedollhouses.com; http://onlinepuppets.org; http://mindfuldraw.com Therapycards on http://oaklandertraining.org.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 In full: ibid.